|

Lislot Frei:

Katharina, als wir uns am Konservatorium Bern kennen lernten, warst

du mitten im klassischen Klavierspiel und weit weg vom Improvisieren.

Was gab den Anstoss zur Improvisation?

Katharina Weber: Ich war Mitglied einer Gruppe für

Neue Musik, zu der auch der Klarinettist Philippe Micol gehörte.

Er fand eines Tages, wir sollten gemeinsam improvisieren. Für mich

war das ungeheuer schwierig, ich hatte bis zu diesem Zeitpunkt –

ich war 17 – nie auch nur einen einzigen Ton frei gespielt, nur

nach Noten, wenn möglich auswendig. Es dauerte sehr lange und schwierige

Jahre, mir den Weg zum Improvisieren frei zu schaufeln, aber weil ich

es unbedingt wollte, unbedingt eine eigene Sprache und Ausdrucksweise

finden wollte, machte ich einfach immer weiter.

Und irgendwann mal mit Erfolg.

Ja, zum ersten Mal war ich zufrieden, als ich und mein Exmann Julian

Trieb in einem Berner Kleintheater eine Woche lang jeden Abend Pantomime

mit Musik spielten. Jeden Abend eine neue Chance, da hat’s dann

geklappt.

Wer hat dich auf diesem offenbar steinigen Weg beeinflusst?

Mein Klavierlehrer Urs Peter Schneider, dann Irène Schweizer,

die mir als Künstlerin und Frau sehr imponiert. Ich habe viele

ihrer Konzerte besucht und später auch mit ihr gespielt, ein sehr

herausfordernder Austausch! Weiter habe ich Kurse bei Vinko Globokar,

Frederic Rzewski, Pauline Oliveros, Fred Frith besucht. Prägend

war aber vor allem das Experimentieren in der Werkstatt für improvisierte

Musik WIM in Bern, da sah man mich eine Zeit lang jede Woche.

Und du hast dich frei gespielt?

Frei gespielt und mehr, wund gespielt, da wurden Mengen von Energie

frei gesetzt!

Wo siehst du dich heute im Dreieck Klassik, Neue Musik und Improvisation?

Überall, und alle drei beeinflussen sich gegenseitig. Kürzlich

ging mir beim Beethoven-Üben durch den Kopf, dass ich diese Intensität

der Emotion auch mal bei meinen eigenen Improvisationen erleben möchte.

Diese Konzentration, diese seelische Ergriffenheit, so weit wie Beethoven

bin ich also noch nicht (lacht).

Was gibt’s denn noch Klassisches in deinen Improvisationen?

Noch? – Ich frage mich, ob nicht immer mehr davon zurückkommt!

Denn das energetische Improvisieren des Free Jazz macht jetzt auch sanfteren

Tönen Platz. Ich höre oft, dass meine Musik nach Zweiter Wiener

Schule klinge, nach Schönberg, Berg und Webern. Das stimmt, ich

suche diese besonderen Intervallbeziehungen, vermeide zum Beispiel meistens

die Oktave und liebe dafür Kombinationen mit der grossen Sept,

wie sie Webern verwendet.

Du komponierst ja auch.

Ja, sporadisch. Eine der ersten Kompositionen war ein Stück für

Solobratsche, das Instrument meiner Mutter, obschon sie das Werk als

Laie nicht spielen kann, dann natürlich Klaviermusik, ein Stück

für Irène Schweizer und mich, und als letztes ein Chorstück,

das allerdings aus Improvisationskonzepten besteht. Ich habe nämlich

grosse Mühe, mich definitiv für einen Ton zu entscheiden.

Zu deinen Stücken: Die Titel hast du erst nachträglich

hinzugefügt, was steht denn am Anfang einer Improvisation? Ein

Bild, eine Struktur, ein Gedanke, ein Ton, ein Intervall?

Ein Klangmaterial. Daraus ergibt sich dann das Stück in seinem

Aufbau, seiner Struktur und Länge. Vor der Aufnahme hatte ich einen

Monat Zeit zum Improvisieren, daraus ist eine Materialsammlung als Grundlage

für diese CD entstanden, obschon auch Improvisationen auf der CD

zu hören sind, die ganz im Moment der Aufnahme entstanden sind.

Was für Material denn?

Zum Beispiel Quinten in «Quint-Essenz». Oder die Metallverstrebungen

des Flügels in «Verstrebungen», die ich mit Schlegeln

bearbeite. In «Gefälschte Obertöne und die Wahrheit

dahinter» spiele ich rechts leise Akkorde und links laute Staccati,

das ergibt einen Obertoneffekt, der in Wahrheit keiner ist. Für

«Spiegelfläche» benutze ich Quintmelodien in Extremlage

und spiegle sie in der Mitte zwischen Hoch und Tief, das ergibt einen

stark verfremdenden Effekt.

Zu mehreren deiner Stücke assoziiere ich Romantisches. Nicht

Schwelgen und Melodienseeligkeit, sondern die Frühromantik der

Zeit Schumanns, die Natursehnsucht damals, die Naturbilder in den Gedichten

Eichendorffs wie etwa der Mond, der sich im Teich spiegelt oder der

Wanderer allein im dunklen Wald. Kannst du mit diesen Eindrücken

etwas anfangen?

O ja, sehr viel, Eichendorffs «Mondnacht» in Schumanns Vertonung

zum Beispiel ist mein romantisches Lieblingslied. Ich hätte allerdings

nicht gedacht, dass ich mit meinen Improvisationen solche Stimmungen

erzeuge, aber es freut mich, wenn du solche Beziehungen darin hörst.

Es gibt ein romantisches Stück auf der CD, «Der Traum der

Gräfin», das mir allerdings fast zu salonhaft in diese Richtung

geht ...

… und mein Lieblingsstück ist. Es ist schön, auch ruhigere

Klänge zu hören.

Auch wahr. Ich habe vorhin von sanfteren Tönen gesprochen. Das

ist ein Erbe Kurtágs, der aus seiner Emotion oder vielleicht

eher aus seiner Intuition heraus komponiert und auch in Bezug auf das

Interpretieren grösste Sensibilität fordert. Er kann aber

auch sehr heftig sein!

György Kurtág ist für dich eine musikalische Herzensangelegenheit.

Ja, eine sehr tiefe Bekanntschaft, um es mal so auszudrücken. Aber

Fred Frith hat Recht mit den Komponisten, die er in meiner Musik hört,

die sind mir alle sehr wichtig. Vielleicht wäre noch die russische

Komponistin Galina Ustvolskaya zu erwähnen.

Kurtágs Musik aber wirkt nicht emotional, sondern sehr konzentriert.

Ich habe mal einen Satz seines ersten Streichquartetts analysiert, der

dauert nur eine Minute, beinhaltet aber unheimlich viel Material und

dessen Verarbeitung. Kurtág versucht, in kürzester Zeit

möglichst viel zu sagen.

Sein Freund György Ligeti hat Kurtágs Musik mal mit

Objekten des französischen Künstlers César verglichen,

der Autos mittels Hydraulik zu kompakten Würfeln mit reichem Innenleben

pressen liess. Aber zurück zu dir. Deine Improvisationen haben

für meine Ohren ein sehr stimmiges Timing, du weisst, wann Schluss

sein muss.

Ja, tatsächlich muss ich mich sogar sehr darum bemühen, dass

ich nicht zu früh Schluss mache (lacht), halt wie beim Sprechen,

denn ich bin eigentlich sehr schweigsam.

Nicht aber in «Der wild gewordene Steinfrosch».

Das ist eine Hommage an Kurtág. Ein Stück im ersten Band

seines Klavierzyklus «Játékok» heisst «Der

Steinfrosch langsam ging» und besteht aus plump daherwatschelnden

Clustern. Cluster sind toll, weil sie so ein musikalisches Urmaterial

sind.

Bei dir rasten sie aber zu unheimlichen Klangballungen aus.

Das liegt an den tiefen Tönen, die Fred Frith in seinem Text erwähnt

und auf denen ich so beharre. Der Grund dafür ist der Flügel,

den ich für die Aufnahmen zur Verfügung hatte. Es ist ein

Bösendorfer Imperial mit zusätzlichen tiefen Saiten, die ich

unbedingt ausnutzen wollte.

Der Klavierklang ist übrigens eher weich und dunkel.

Ja, eine sehr farbige und samtene Klanglichkeit. Im Aufnahmeraum des

Olaf-Åsteson-Hauses in Hinterfultigen stand übrigens ein

plätschernder Zimmerbrunnen, den habe ich im «Dialog mit

dem Hausgeist» verewigt.

Atmosphäre ist sowieso ein Thema, zum Beispiel in «Bebung»,

wo die ersten Töne die Bühne für ein wuselndes Durcheinander

freigeben.

Da beziehe ich mich auf eine barocke Technik, mit der ein langer Ton

moduliert und in ein leichtes Vibrato, eben eine Bebung, versetzt wird.

Dies ist ein Mittel, um das Manko des Klaviers zu beheben, das keinen

langen Ton halten kann.

Auffällig finde ich dein Insistieren. Du gehst oft unbeirrt

den einmal eingeschlagenen Weg, nicht gerade stur, aber doch mit Ausdauer,

und führst mich damit als Hörerin. Oder du bleibst bei einem

Klang und schaust, was passiert, zum Beispiel in «Säulengänge».

Das ist so und das ist wichtig. Es geht manchmal darum, ein Objekt von

den verschiedensten Seiten zu betrachten. Zu fragen, was alles in einem

sehr beschränkten Material steckt, ist auch eine meditative Aufgabe.

«Was bleibt?» ist ein philosophischer Titel für

eine Musik mit wenigen tastenden Tönen.

… die sich nochmals auf Kurtág bezieht. In seinen Kafka-Fragmenten

gibt es das Stück «In memoriam Joannis Pilinszky» mit

folgendem Text: «Ich … kann nicht eigentlich erzählen,

ja fast nicht einmal reden; wenn ich erzähle, habe ich meistens

ein Gefühl, wie es kleine Kinder haben könnten, die die ersten

Gehversuche machen.»

Lislot Frei ist Musikredaktorin beim Schweizer Radio

DRS 2.

Lislot Frei: Katharina, when we met at the Bern Conservatory,

you were totally focused on classical piano playing and did not do any

improvising at all. What led you to pursue improvisation?

Katharina Weber: I was a member of a New Music group

with the clarinetist Philippe Micol. One day, he thought it would be

good for us to improvise together. It was incredibly hard for me; until

then (I was 17), I’d never played a single note without sheet

music, and mostly from memory. It took me a long, long time, and many

difficult years, to find a way into improvisation for myself, but since

I absolutely wanted to do it, absolutely wanted to find my own language

and my own mode of expression, I just kept on trying.

And, in the end, you did it.

Yes, the first time I was satisfied was when my ex-husband Julian Trieb

and I accompanied mimes in a small Bern theater, every evening for a

week. Every evening a new opportunity, and then it clicked.

Who influenced you on your apparently quite rocky road to improvisation?

My piano teacher Urs Peter Schneider, then Irène Schweizer, who

had a lot of influence on me both as an artist and as a woman. I went

to a lot of her concerts and later played with her too – a very

challenging exchange! I also took courses with Vinko Globokar, Frederic

Rzewski, Pauline Oliveros, and Fred Frith. But what influenced me most

was experimenting at the Workshop for Improvised Music (WIM) in Bern;

I went there every week for quite a while.

And you played yourself into free music?

Played myself into it, and played myself raw – huge amounts of

energy are released there!

Where do you see yourself now in the triangle of classical music,

New Music, and improvisation?

Everywhere, with all three influencing each other. Recently, while I

was practicing Beethoven, it crossed my mind that I’d like to

experience the same emotional intensity at some point during my own

improvisations. That concentration, that sense of being moved spiritually

– so I haven’t gotten as far as Beethoven yet (laughs).

What is still classical in your improvisations?

Still? – I wonder whether more and more of them might be returning

to the classical! You see, my energetic Free Jazz improvising is now

giving way to gentler sounds. I’m often told that my music sounds

like Second Viennese School, like Schönberg, Berg, and Webern.

That’s true; I look for the same special interval relationships;

for example, I mostly avoid the octave, prefering combinations with

the major seventh instead, as in Webern.

You also compose music.

Yes, sporadically. One of my first compositions was for solo viola,

my mother’s instrument, although as an amateur she cannot play

the work. And then piano music, of course, a piece for Irène

Schweizer and me, and finally a choral piece, but one consisting of

ideas for improvisation. You see, I have a really hard time making definitive

decisions in favor of particular notes.

Let’s talk about your pieces: you added the titles only after

recording them, so how does an improvisation begin? With an image, a

structure, an idea, a sound, an interval?

A concrete bit of sound the piece then comes out of, in its development,

its structure and length. Before the recording, I had one month to improvise,

and I put together a collection of material to be a basis for the CD,

although it also includes improvisations that came about entirely during

the recording itself.

What kind of material did you collect?

For example, fifths in “Quint-Essenz”. Or the metal struts

[Verstrebungen] of the piano in “Verstrebungen”, which I

played with sticks. In “Gefälschte Obertöne und die

Wahrheit dahinter” [Faked Overtones and the Truth behind Them],

I play quiet chords on the right and loud staccatos on the left, creating

an apparent overtone effect that doesn’t actually involve overtones

at all. For “Spiegelfläche” [Mirror Surface], I use

fifth melodies in extreme ranges and reflect them in the middle between

the high and the low, which makes everything sound quite strange.

I associate something Romantic with quite a few of your pieces.

Not indulgence and melodic bliss, but the early Romanticism of the age

of Schumann, the longing for nature back then, the natural images in

Eichendorff’s poems, such as the moon reflected in the pond or

the wanderer alone in the dark forest. Do you have any response to these

impressions?

Yes, I do! Schumann’s setting of Eichendorff’s “Mondnacht”,

for example, is my favorite Romantic song. Still, I wouldn’t have

thought I produced such moods in my improvisations, but I’m pleased

if you have such associations when you listen to them. One piece on

the CD, “Der Traum der Gräfin” [The Countess’s

Dream], is surely Romantic, even if I find it gets a bit too close to

the salon ...

... and is my favorite piece. It’s a pleasure to hear quieter

sounds, too.

That’s true, too. I did talk about gentler sounds before. I got

that from Kurtág, who composes from his emotions, or perhaps

more from his intuition, and demands great sensitivity of interpretation,

too. But he can also be very heavy!

György Kurtág is one of your great loves in music.

Yes, there’s a very deep connection there – just to put

it like that for once. But Fred Frith is right about the composers he

hears in my music; all the ones he mentions are very important to me.

Perhaps the Russian composer Galina Ustvolskaya should added to the

list.

But Kurtág’s music doesn’t seem emotional, just very

concentrated.

I once analyzed a movement from his first string quartet that lasts

only one minute – but it contains and develops an amazing amount

of material. Kurtág tries to say as much as possible in a very

short amount of time.

His friend György Ligeti once compared Kurtág’s music

with objects by the French artist César, who uses hydraulic presses

to have cars crushed into compact cubes with a complex inner life. But

let’s talk about you some more. To my ears, your improvisations

have a very coherent sense of timing – you know when the end should

come.

Yes – and I even have to try very hard to not stop too soon (laughs),

just like when I’m talking, for I’m actually a very quiet

person.

But not in “Der wild gewordene Steinfrosch” [The Stone-Frog

Gone Wild].

That’s a homage to Kurtág. A piece in the first volume

of his piano cycle “Játékok” [Games] is called

“The Stone-Frog Crawled Along,” and it has all these clumsily

waddling clusters. Clusters are great because they’re such primary

musical material.

But in your work they explode into uncanny pile-ups of sound.

That’s because of the low notes Fred Frith mentions in his text,

sounds I dig so deep into. The piano I had for the recordings led me

to do that. It’s a Boesendorfer Imperial with additional low strings,

which I absolutely wanted to use.

But the piano sound is softer, darker.

Yes, a very colorful, velvety timbre. In the studio at the Olaf Åsteson

House in Hinterfultigen, by the way, there was a bubbling indoor fountain

that inspired my “Dialog mit dem Hausgeist” [Dialogue with

the Household Ghost].

In any event, atmosphere is a theme, as in “Bebung”

[Trembling], where the first tones set the stage for teeming chaos.

There, I was alluding to a baroque technique that modulates a long tone

and turns it into a slight vibrato – that is a trembling. This

is a way to overcome the fact that the piano cannot sustain a longer

tone.

I am struck by the insistent quality of your playing. You often

pursue your initial course without flinching—not really stubbornly,

but with endurance, thus leading me as I listen. Or you stay with a

sound and see what happens, as in “Säulengänge”

[Arcades].

That’s right, and it’s important. Sometimes, it’s

a matter of looking at an object from as many different perspectives

as possible. Seeing how much can be drawn out of very limited material

is also a kind of meditation.

“Was bleibt?” [What Remains?] is a philosophical title

for music with only a few groping notes.

… which is also a reference to Kurtág. In his Kafka fragments,

in the piece “In memoriam Joannis Pilinszky,” there’s

the following text: “I … actually can’t tell stories,

can hardly even talk; when I do tell stories, I mostly feel like little

children must when they take their first steps.”

Interview by Lislot Frei. Translation by Andrew Shields

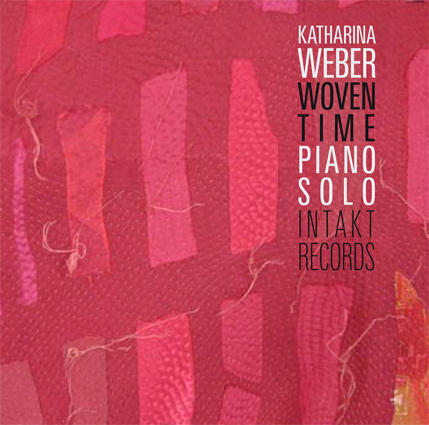

Liner Notes, Intakt

CD 157.

Katharina

Weber on Intakt Records

|