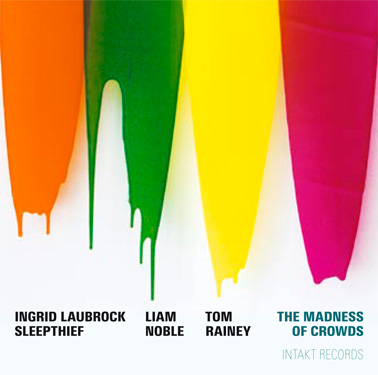

INGRID LAUBROCK SLEEPTHIEF

The Madness of Crowds

To begin at the beginning. Nichts fürchtet der Mensch mehr als die Berührung durch das Unbekannte. A screaming comes across the sky – lauter erste Sätze: Dylan Thomas, Elias Canetti, Thomas Pynchon. Sätze, die vom Welttheater im Mikro-Format erzählen, von der Masse und der ihr innewohnenden panischen Neigung, oder vom tönenden Beginn einer Katastrophe. Vertraut erscheinen sie, und doch erreichen sie uns wie von fern – aus der Dunkelkammer der kollektiven Erinnerung, aus dem düsteren Labyrinth der Ahnung. Dort, wo auch Charles Mackay siedelt, Autor des Buches "Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds", auf das sich Ingrid Laubrocks Titel so bedeutungsvoll und doch en passant beziehen.

Entsprechend leise erklingen denn auch die ersten Töne, ein langsames Sich-Vortasten in einen Bewußtseinsraum, den diese Klänge nach und um so selbstbewußter besetzen – um sich dann wieder für einen Moment in den Hallraum der Ferne zurückzuziehen. Andeutungen, planvoll hingeworfene Skizzen: Es ist als würde die Nacht der Stille von Klängen erleuchtet, in denen Gegenwart und Erinnerung zueinander finden. Imaginäre, traumverlorene Räume sind es, die Ingrid Laubrock, Liam Noble und Tom Rainey hier gestalten – fein gestaffelte Klangdistanzen, eine ständige Verschiebung von Vorder- und Hintergrund, oszillierende Bewegungen zwischen alptraumhafter Langsamkeit und insistierender Aufwallung.

Jenes große Formgefühl, mit dem das Trio aus der freien, momentgebundenen Improvisation heraus seine Stücke gestaltet, war bereits auf dem ersten Sleepthief-Album zu bewundern. Eine Musik erhob sich hier, in wunderbar nuancierter Tonkultur, die alle Kategorisierungsversuche zum Scheitern verurteilen mußte. Denn die artistische Passion, mit der sich die drei Musiker einer Poesie des durchdacht Vorläufigen hingaben, bot mehr als nur einen Blick in eine Welt unendlicher Spiel- und Kombinationsmöglichkeiten. "The Madness of Crowds" nun erscheint riskanter, bar jeder Routine, die sich in der Zwischenzeit eingestellt haben könnte. Stattdessen gründet dieses Risikospiel der Rückhaltlosigkeit, diese Wanderung entlang des Abgrundes gerade in einem Vertrauen auf den individuellen Mut zur ständigen Verwandlung und Reflexion der kollektiv entwickelten Ideen. Hier gibt es keine kompositorische Absicherung, die als Nothalt und Fluchtpunkt dienen könnte: in diesem Wagnis zählt allein der Augenblick, den sich alle drei teilen.

Es ist jener schwindelerregenden Glanz des Augenblicks, wie Jean-Paul Sartre einmal über den Jazz schrieb, der den Kern der Improvisation ausmacht, diese große Kunst des Vergessens; die Konzentration auf eine Intuition, die erst über die Brechung am Intellekt ihre ästhetische Legitimation erhält: "Gefühle und Ahnungen haben alle möglichen Leute. Was einen Künstler von ihnen unterscheidet, ist, daß er seine Gefühle formulieren kann. Formulieren mit Hilfe von klaren Berechnungen. Ich weiß sehr genau, daß der Kern der Kunst Magie ist. Aber dieser Kern kann nur durch äußerste Klarheit, durch eine Rationalisierung der Mittel sichtbar gemacht werden. Wenn ich will, daß die Zuhörer etwas fühlen, muß ich selbst kühl bleiben." So formulierte in einer Skizze von Alfred Andersch der (fiktive) Jazz-Schlagzeuger Mondor bereits 1965 ein Problem, das sich seine Scheinhaftigkeit bis heute bewahrt hat: den Widerspruch von Gefühl und Intellektualität. Ein Antagonismus, den Ingrid Laubrock souverän als vorgeblichen zu enthüllen versteht.

Jazz, als vorwiegend improvisierte Musik begriffen, ist eine bewußte Art der Heimatlosigkeit, der sein Referenzsystem heute im Imaginären sucht und sich einer einfachen Rückführung auf prägnant formulierbare Einflußsphären verweigert. Denn Improvisation ist in ihrem Wesen eine selbstvergessene Überschreitung der Erinnerung; eine Überschreitung, die in der Freiheit der Imagination geschieht ¬– und somit der vollkommenste Ausdruck einer Individualität ist, die sich das Recht nimmt, sich der Bewegung und den Regeln der Masse zu widersetzen. Jenen von Mackay oder Canetti beschriebenen Mechanismen des kollektiven Massenwahnsinns und den sich darin konkretisierenden Strukturen der Macht begegnet das Trio mit einem Spiel kalkulierter sowie intuitiver Vielsprachigkeit: ein feingesponnenes Netz gelebter Paradoxa, ein Ineinanderfließen miteinander konkurrierender Ideen – eine Bewegung von Konzentration und Abschweifung, die Erkundung lyrischer Weiten und plötzlichen Eruptionen. Musik konkretisiert sich in diesem Trio als eine freie Zirkulation von Klang- und Ideenströmen, die noch einmal – wie so oft in der improvisierten Musik – mit spielerischer Leichtigkeit von der Utopie einer offenen Individualität erzählen. Eine Leichtigkeit, die erst aus einem hartnäckigen, arbeitsvollen Ernst heraus zu gestalten ist.

Harry Lachner, München 2011

INGRID LAUBROCK SLEEPTHIEF

The Madness of Crowds

To begin at the beginning. There is nothing that man fears more than the touch of the unknown. A screaming comes across the sky – these are all opening sentences: Dylan Thomas, Elias Canetti, Thomas Pynchon. Sentences, telling of the world theatre in micro format, of the masses and their inherent tendency towards panic, or of the sounds which herald a catastrophe. They seem familiar, yet they still reach us as if from far away – from the dark-room of the collective memory, from the disconsolate labyrinth of premonition. And this is also where Charles Mackay is located, author of the book "Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds", the book Ingrid Laubrock's title refers to en passant and yet in such a meaningful way.

Appropriately soft, the first tones resonate, a slow step-by-step approach into an area of consciousness in which these sounds then, even more self-confidently, gradually take up – again drawing themselves back into the reverberant space in the distance for an instant. Allusions, sketches methodically tossed in: It is as if the night of silence was lit up by sounds, in which the present moment and the recollections find each other. These are imaginary spaces, lost in reverie, which Ingrid Laubrock, Liam Noble and Tom Rainey create – finely graded dispersions of sound, a constant shifting of background and foreground, oscillating movements between nightmarish drawl and insistent surge.

This vast sense of form from which the trio creates its pieces out of the free improvisation bound to the moment, was already to be admired on the first Sleepthief album. There, a kind of music arose, in a wonderfully multi-faceted sound culture, which defied any attempt at categorization. Here the artistic passion with which the three musicians committed themselves to a kind of poetry of intentional evanescence, offered more than just a glimpse into a world of infinite possibilities of playing and of combinations. Now, "The Madness of Crowds" seems a more risky proposition, lacking any routine which could have developed in the meantime. On the contrary, this risky game of nonchalance, this wandering along the edge of the abyss is implicitly based on trusting the individual's courage to change constantly and to reflect upon collectively developed ideas. There is no compositorial safeguarding here which could serve as emergency stop and escape: the only thing that counts in this risky business is that instant shared by all three.

It is this staggering splendour of the moment, as Jean-Paul Sartre once wrote about Jazz, which constitutes the core of improvisation, this high art of forgetting; concentration upon a kind of intuition which only achieves its aesthetic legitimation through a breach in the intellect. "All sorts of people have emotions and premonitions. What distinguishes the artist from them is the fact that he is able to formulate his feelings. Formulate them with the help of clear consideration. I know very well that magic is the essence of art. However, this core can only be made visible by the utmost clarity, by rationalization of the means. If I want the audience to feel something, I myself have to stay cool." This is how the (fictitious) Jazz drummer Mondor, already in 1965, in a draft by Alfred Andersch, formulated a kind of problem which has retained its elusiveness right up to the present day: the contradiction between emotion and intellect. An antagonism, Ingrid Laubrock supremely manages to reveal as purely putative.

Jazz, conceived as a predominantly improvised music, is a deliberate way of being homeless. These days it is looking for a reference system in the imaginary, refusing a simple reduction to spheres of influence which can be succinctly formulated. And as improvisation is, by its very nature, an oblivious transgression of memory; a transgression happening within the freedom of the imagination – thus becoming the most complete expression of a kind of individuality which feels itself entitled to defy the movements and rules of the masses. Those mechanisms of collective mass insanity as described by Mackay and Canetti, and the structures of power which manifest themselves within them, are dealt with by the trio through its more deliberated as well as intuitive multi-linguistic playing: a finespun network of prevailing paradoxes, a flowing together of competing ideas – a movement of concentration and divagation, exploration of lyrical reach and sudden eruptions. In this trio, music manifests itself as a free circulation of streams of sounds and ideas, which once again – as is often the case in improvised music – with playful ebullience tells of the utopia of open individuality. The kind of ebullience which can only arise out of a determined and indefatigable commitment.

Harry Lachner

Translation: Isabel Seeberg

Ingrid Laubrock on Intakt Records