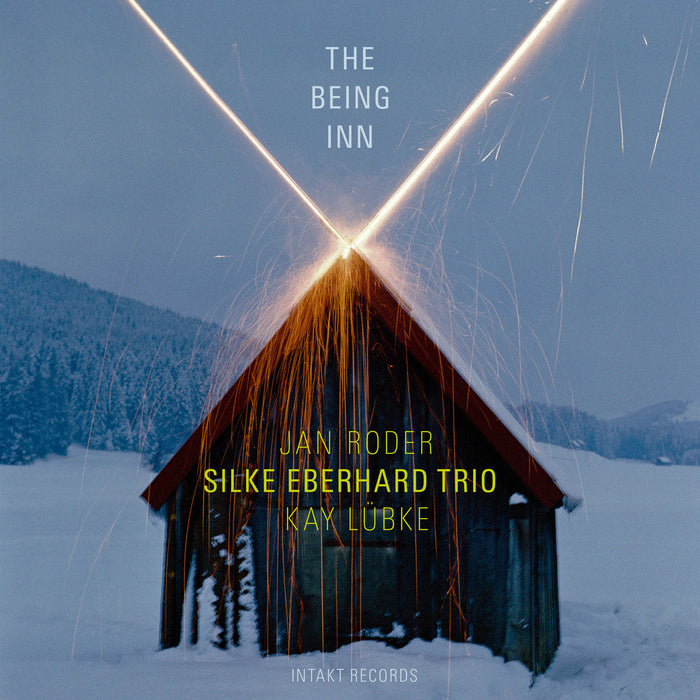

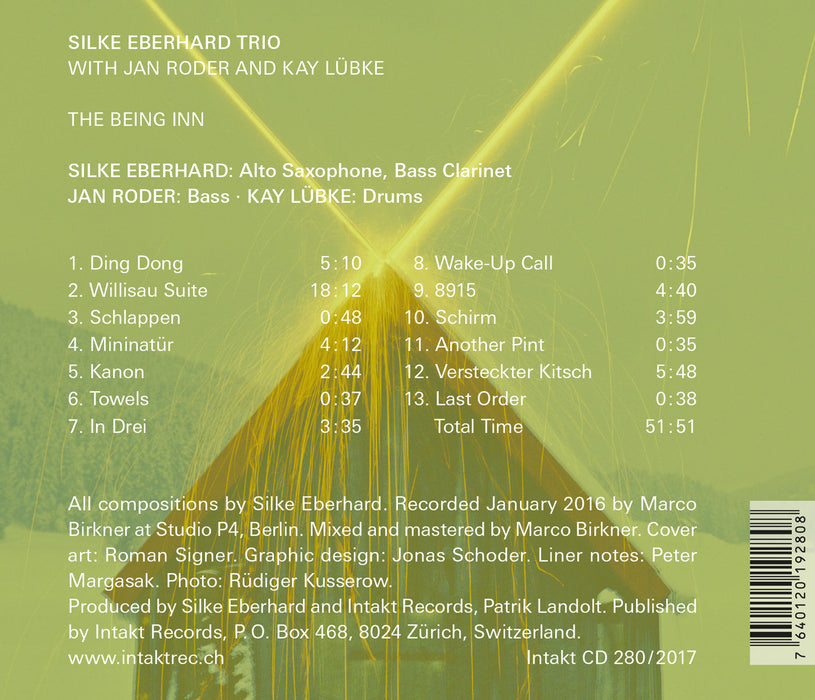

280: SILKE EBERHARD TRIO. The Being Inn

Intakt Recording #280/ 2017

Silke Eberhard: Alto Saxophone, Clarinet, Bass Clarinet

Jan Roder: Bass

Kay Lübke: Drums

Recorded January 2016 by Marco Birkner at Studio P4, Berlin.

More Info

It’s no secret that reedist Silke Eberhard is a keen student of jazz history, a player whose inspiration routinely gets recharged by immersing herself in the music of her early heroes. For her that means more than listening to old records by the likes of Eric Dolphy, Charles Mingus, and Ornette Coleman (the subject of Eberhard’s 2007 Intakt debut, a duo album with pianist Aki Takase titled Ornette Coleman Anthology) – but diving into that repertoire and reshaping it with novel instrumentation. But Eberhard makes it clear that the trio featured on The Being Inn is the context for which she always imagines her own material. “I feel a lot of freedom with this group,” she says of working with bassist Jan Roder and drummer Kay Lübke. Although this particular group coalesced in 2006, her history with each player stretches back to the mid-90s and there’s no missing the rapport they’ve all developed together.

Eberhard and company make a conceptual leap on the album, with many of the pieces tied to the titular concept – an imaginary inn the Saxophoneophonist pictured as she composed numerous tunes. She jokes that the spry opening track, “Ding Dong,” is the kind of number she likes to open one of the trio’s sets with – “a door bell,” she calls it, although the first sounds we actually here are her footsteps leading toward a door that soon opens, inviting the listener in. (Peter Margasak, from the liner notes)

Album Credits

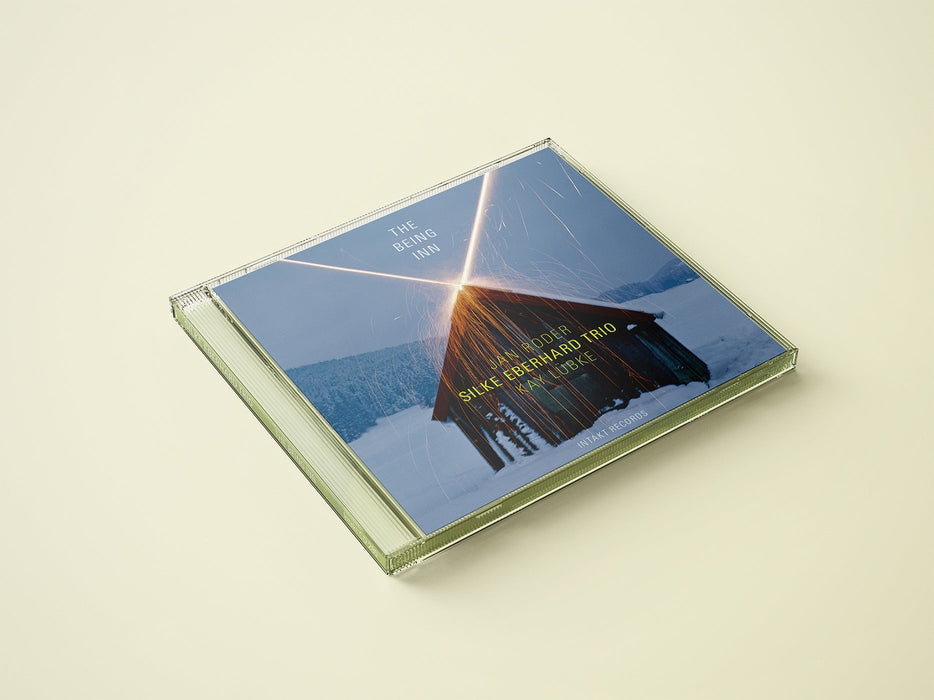

Cover art: Roman Signer

Cover design: Jonas Schoder

Liner notes: Peter Margasak

Photo: Manuel Miethe

All compositions by Silke Eberhard. Recorded January 2016 by Marco Birkner at Studio P4, Berlin. Mixed and mastered by Marco Birkner.

Plus âgée que sa compatriote d’une quinzaine d’années, la quadragénaire Silke Eberhard (« The Being Inn ») est quant à elle restée en Allemagne où elle occupe depuis quelques lustres une place notable au sein de la scène nationale. La sonorité de son alto (elle pratique aussi la clarinette basse) est plus tranchante que celle de Charlotte Greve et c’est en leader qu’elle s’affiche avec un trio dont elle compose l’intégralité du répertoire. Elle y est accompagnée par les excellents Jan Roder (b) et Kay Lübke (dm) dont le jeu dynamique convient parfaitement aux improvisations fureteuses de la souffleuse.

https://blogdegarenne.blogspot.com/2020/10/gender-stories-2.html

Beaucoup plus aéré est le disque d’un second trio sax-contrebasse-batterie, celui de la saxophoniste allemande Silke Eberhard (saxo-alto et clarinette basse), fort bien accompagnée par Jan Roder et Kay Lübke. Son jeu, sinueux, son attaque franche, et son travail sur les intervalles renvoient un peu à Eric Dolphy, à Steve Lacy également, et peut-être à Arthur Blythe car elle navigue sur des thèmes et des structures rythmiques assez simples, mais parfaits pour susciter l’improvisation. Une suite de 18’, sept pièces qui n’atteignent pas 6’, et cinq intermèdes de 30/40’’ où le même thème est joué dans différentes tonalités, constituent un très bon disque de jazz contemporain. Silke Enerhard s’était déjà signalée avantageusement à nos oreilles dans des duos avec pianistes : Aki Takase « Ornette Coleman Anthology » (Intakt 129) et Uwe Oberg (cf. Culturejazz « Une année avec Leo (1) » 16/12//2016) et avec le trio I’m Three « Mingus, Mingus, Mingus » (LR 752 2016) . On voit qu’elle puise aux meilleures sources.

https://www.culturejazz.fr/spip.php?article3360

Det starter med at vi hører saksofonisten Silke Eberhardt gå fra venstre til høyre høyttaler på sine høyhælede sko, før trioen med henne på altsaksofon, bassisten Jan Roder og trommeslageren Lay Lübke setter an i noe som kunne vært hentet fra en av platene til Henry Threadgill og hans AIR-prosjekt.

Men her er all musikken laget av Eberhardt, som er godt bevandret innenfor den moderne delen av den europeiske jazzen med en rekke prosjekter, som for eksempel hennes strålende hyllest til Ornette Coleman i duo med pianisten Aki Takase, og med Eve Rissers store orkester, for å nevne et par av høydepunktene.

Og at akkurat hun har gjort en hyllest til Ornette Coleman virker svært naturlig når man hører hennes spill. Det er mye Coleman i spillet, men kanskje like mye de andre saksofonistene som fulgte i sporene etter Coleman, og som fulgte hans ideer og musikalske retning. Som for eksempel Henry Threadgill.

Eberhardts tone i altsaksofonen er relativt lys, men hun trakterer også bassklarinett på denne innspillingen, et instrument man i første rekke forbinder med Eric Dolphy, en musiker fra 60-tallet som Eberhardt kjenner godt. I tillegg kan man også høre referanser til Charles Mingus, noe som, selvsagt kan ha noe med Mingus sitt nære samarbeid med Dolphy i noen år.

Med Jan Roder som fjellstø bassist, som sender avgårde flere strålende solier gjennom hele platen, og Kay Lübke som sprelsk, kreativ og spennende trommeslager, sammen med Eberhardts klare referanser til 60-tallets helter, får vi en flott kombinasjon av nyere jazz og tradisjonene som fungerer perfekt.

Alle tre kommuniserer nærmest perfekt, vi har med tre strålende musikere å gjøre, og sammen har de laget et album som oser av kvalitet, energi og spennende samspill. Og sitter du på Henry Threadgills AIR-plater, og er ute etter mer i samme landskapet, så er dette den perfekte platen å skaffe seg.

Anbefales til alle venner av heltene fra 60-tallet, som gjerne vil høre hvor den musikken har havnet.

https://salt-peanuts.eu/record/silke-eberhardt-trio/

Quarantacinque anni, tedesca di Heidenheim an der Brenz (ma ormai di stanza a Berlino), Silke Eberhard guida da alcuni anni il trio protagonista di questo album, diretto, corporeo, al cui interno il suo contralto (più di rado il clarone) si distende con estrema libertà, di misura e di dizione, con un senso della forma che definiremmo sostanzialmente veicolato al singolo episodio (e alcuni sono brevissimi, poco oltre il mezzo minuto) e il risultato, di conseguenza, che un disco senz'altro di lodevole fattura finisce via via per scorrere un po' prevedibile, scontato, lievemente schematico.

L'idioma è un free-bop—secondo una definizione che ebbe un certo seguito anni fa—non esageratamente spericolato (tutti della sassofonista i tredici brani in scaletta), forte di sonorità per lo più nette, anche acuminate, e un procedere d'insieme (generalmente a ranghi compatti) che ha momenti anche tumultuosi, tendenzialmente affermativi, estroversi ma senza eccessi. Da ricercare fra i brani dispari (l'iniziale "Ding Dong" e poi "Schlappen," "Kanon" e "8915") i momenti più significativi che il disco ci offre.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/the-being-inn-silke-eberhard-intakt-records-review-by-alberto-bazzurro

Nicht ganz zu Unrecht erinnert das Silke Eberhard Trio an das Ensemble, mit dem Sonny Rollins in den fünfziger Jahren das Format Bass-Saxophon-Schlagzeug begründete. Das seit 2006 bestehende Trio der Berliner Altsaxophonistin bezieht sich zwar nicht explizit auf Rollins, den Giganten, dessen Geist ist aber spürbar. Eberhards Kompositionen entspringen, wie sie bereits mehrfach bewiesen hat, dem Geist Eric Dolphys, Charles Mingus' oder Ornette Colemans.

Auf dem neuen Album sind über ein Dutzend stimmungsvoller Stücke versammelt, denen sich der Hörer nicht entziehen kann. Dieser wird unvermittelt mit einem witzigen „Ding Dong" ins imaginäre Gasthaus (The Being Inn) geführt, das auf dem Cover mit einer Holzhütte angedeutet wird. In einer Holzhütte fand einstmals das Jazz Festival Willisau statt, dem Eberhard mit der 18-minütigen Willisau-Suite Tribut zollt. Auch die „Schweizer Naturwelt", die Eberhards einmonatige Residenz in Willisau ebenso reflektiert, wird von den Instrumentalisten berücksichtigt. Bassist Jan Roder und Schlagzeuger Kay Lübke fügen sich glänzend ein. Hard- bop reinsten Wassers mit expressiven Zügen.

Part of the ever-burgeoning stratum of Berlin-based improvisers, alto saxophonist/bass clarinetist Silke Eberhard doesn’t limit herself to any one band or musical configuration. In fact she has partnered with players across the age spectrum from pianist Ulrich Gumpert to trombonist Matthias Müller. Additionally, while her ensembles usually concentrate on original material, she has also recorded interpretations of classic works by Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy and others. These trio discs succinctly reflect her bilateral approach. Together since 2006, the trio of the reedist, bassist Jan Roder and drummer Kay Lübke plays 13 of Eberhard’s own compositions on The Being Inn, while I Am Three, completed by trumpeter Nikolaus Neuser and drummer Christian Marien tries its hand on a dozen of bassist Charles Mingus’ pieces on the other CD.

Mingus Mingus Mingus appears to be aiming for a snarky, punk-like reappraisal of the bassist’s work, and can be commended for reviving more obscure Mingus tunes as well, as his greatest hits. At the same time the lack of a chordal instrument and the undue prominence of Marien, who has been associated with Müller and bassist Clayton Thomas, almost makes it seem as if the horns are accompanying him. Lübke, who has recorded with bands led by reedists Ernst-Ludwig Petrowsky and Uli Kempendorff, and Roder, whose groups have included Die Enttäuschung, provide more equitable contributions to the other session, making the performances more balanced.

Demonstrating this three-pronged approach, the trio is most effusive on “Willisau Suite”, which at 18 minutes plus is almost twice the length of the next two longest tracks combined. A real suite, it moves from a splintered and shuffling introduction through a variety of duos and trios in tandem and in counterpoint, to end up a pleasing amble, encompassing cymbal shakes and a walking bass line. After a drum roll introduces bugle-call-like stuttering from Eberhard, her timbres accelerate to altissimo as she gesticulates theme variation on theme variation, Roder plucks and string pops with a watchmaker’s attention to detail, and is soon joined with equivalent rhythm precision by Lübke. When the percussionist eventually toughens his attack with New Thing-like rotary stick work the reedist’s irregular vibrations and honking eventually splutter to a moderato finale.

Among the aural light and darkness propelled by the trio during a series of short (staring at 38 seconds) and longer (a maximum of nearly six minutes) improvisations are other instances which let the three demonstrate their instrumental prowess. “8915” and “Schirm” for instance, confirm Eberhard’s debt to Dolphy, with an innate rhythm section swing on the former interrupted by a reed squall; while the bassist’s alternating high and low pulses and the drummer’s clockwork-like beats on the latter pace moody mellowness portrayed by Eberhard’s on the second. Simple and bracing, the bass clarinet solo on “Kanon”, tracked only by the drummer, shows how a profound idea can be expressed without massive elaborations. The contracts between the trios are most obvious with the other group’s treatment of the equivalent “Canon” on Mingus Mingus Mingus. While suitable as a final track, it appears more concerned with Marien’s heavy drumming then Neuser’s ex cathedra elaborations.

Otherwise the performances, recorded six months after the first disc, seem to swerve from POMO archness to livelier interpretations. A couple of tracks appear distantly lo-fi, hopefully a salute to Mingus’ 1950s mono records rather than a studio glitch; while a rather solemn reading of “Jelly Roll” is prefaced by the static and crackle of a stylus hitting a well-worn LP groove in a way that detracts from the overall performance. Plus it’s certain that its composer didn’t figure that the profound sentiments of “Self-Portrait in Three Colors” would be expressed by an explicit back-beat drum solo that has more in common with John Bonham than Dannie Richmond.

When the group pays fealty to the Mingus canon, the results aren’t that encouraging either. Performances such as “Oh Lord, Don’t Let Them Drop That Atomic Bomb on Me” or “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” come across as Mingus-lite, with musical nourishment stripped from them along with extraneous calories. Bludgeoned with percussion pressure, the trio doesn’t realize that the first tune is supposed to be played with satiric humor. The second is also a celebration not a dirge and is also weakened when the trumpeter’s exposition is close to “Taps”.

Nimble elsewhere, the band’s interpretations are more notable when it recasts other tunes, almost ignoring the originals. While Neuser’s exaggerated blowing reference Louis Armstrong rather than Ted Curson on “Fables of Faubus”, he later harmonizes perfectly with Eberhard’s alto saxophone and construct an original bent-note finale. As well, “Moanin’” is probably the liveliest cut with snorting saxophone smears doubling plunger trumpet l...

独のフリー系女性リード奏者が活動の柱とするトリオの新作

高瀬アキとの共同名義によるオーネット・コールマン曲集で知られるエバー ハルトが、今回は全曲を作曲。オーネットとエリック・ドルフィーを土台にし たアルトは、現代的なスピード感も兼ね備えて自由自在に飛翔する。1分未満 の演奏を5曲点在させて場面転換のメリハリをつけた構成が特色。2012年 のスイス ス《ヴィリザウ・ジャズ祭》でレジデンス・アーティストを務めた時に 書いた②は、対照的に18分超の組曲で、トリオの魅力を集約。

Om met de deur in huis te vallen: The Being Inn' roept bij deze luisteraar gemende gevoelens op. Enerzijds is er bewondering voor het inventieve en geestdriftige samenspel. Voor de ideeënrijkdom van vooral rietblazer Silke Eberhard. Voor haar lichte, speelse toon die camoufleert hoe hard er moet worden gewerkt. Voor de manier waarop ze nadrukkelijk maar niet koket of blasé laat horen dat ze haar klassiekers kent. Voor de fantasievolle aanpak en het even verbeeldingsvol doortrekken van de lijn Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy naar nu. Hoewel dat nu zit bij deze luisteraar de appreciatie het meest in de weg. Niet in een fraai lichtvoetig stuk als Miniatür maar wel in een paar andere. Leunen op het verleden is niet erg, toch roepen vooral de door free jazz gevoede exploraties de vraag op, hoeveel kans op ontwikkeling die stiel biedt. Zelfs bij een even intelligente als gevoelige blazer als Eberhard liggen constant de citaten en herhalingen op de loer. Dan is er nog de contradictie dat deze muziek bevrijd wilde zijn en wilde bevrijden, dat juist deze muziek als een gegeven wordt genomen, lets waarop kan worden voortgeborduurd. Misschien vraagt deze muziek een conceptuele aanpak van de beschouwer, zoals een kunstenaar die op Mondriaan voortbouwt vragen kan oproepen over de haalbaar-en wenselijkheid om op Mondriaan voort te bouwen. Misschien zijn ook gemende gevoelens niet erg, maar zeker zijn er vragen.

https://www.jazzmo.com/recensie/silke-eberhard-trio-the-being-inn/

Die Intaktler, mit den 'Intakt in London/London in Zürich'-Festivitäten in den stolzen Knochen und zusätzlich bestärkt durch den Preis der deutschen Schallplattenkritik für "Sakura" von Aki Takase & David Murray, kehren ins alltäglichere Geschäft zurück mit The Being Inn (Intakt CD 280). Was will uns das neue Geschwisterchen von "Being" (2008) und "What A Beauty Being" (2011) sagen? Dass nicht Sprache, sondern Musik das Haus des Seins ist? Und sich bei näherer Betrachtung als Kneipe erweist, in der 'Another Pint' und 'Versteckter Kitsch' gezapft, aber vor allem Coleman, Dolphy und Mingus ausgeschenkt werden? Vom Lübecker Berliner Jan Roder am Bass, den wir zuletzt ganz glücklich mit JR3 hörten, und dem Karlsruher Berliner Kay Lübke (von Hornbeef) an den Drums als bewährten Thekenkräften. Mit Silke Eberhard, einer nicht gerade typischen Prenzlschwäbin, die mit Altosax & Bassklarinette und mehr als Freundin denn als Chefin den Ton angibt. Sie schreitet - hörbar - zur Tat, aber dem zu 'Take Five'-ähnlichem Groove gekrähten 'Ding Dong' zu Beginn folgt nicht 'die Hex ist tot', sondern die 18-min. 'Willisau Suite'. Die Hommage an Nikolaus Troxlers Lebenswerk mischt Schweizer Impressionen mit jazzgeschichtlichen Reminiszensen, mit markantem Bogenspiel, rollendem Drive, joggendem oder scharwenzelndem Pizzikato, flippernder Perkussivität, ostinatem Stau und all der kapriziösen und gepfefferten Sangeskunst, zu der Eberhard geradezu altmeisterlich fähig ist. In der anschließenden Lang-Kurz- / Bier-Schnaps-Folge flotter Cheerios und kleiner, sich gleichender Intermezzi auf ex kommen 'Schlappen' und 'Kanon' mit Bassklarinette daher, 'Miniatür' filzweich und mit Besenstrichen. Aber warum die vertrackte und freigiebige Spielkunst der drei verkürzen auf hier ne Repetition (die wie vor ner roten Ampel auf der Stelle tritt), da das raffinierte Wechselspiel von tanzenden Lippen, Fingern oder Stöcken und dort ein Tirili - meist ja schon innerhalb eines Stückchens? Eberhard zeigt sich im spritzig Liquiden forellig wohl und singt auch noch, wenn bei 'Schirm' dunkle Wolken wankend näher rücken. Der Kitsch allerdings, der fällt, schnipp-schnapp, der Schere zum Opfer. Lieber noch n schneller Absacker... - Aaah.

Silke Eberhard, die sich auf früheren Alben intensiv mit Ornette Coleman oder Eric Dolphy befasst hat und sich von ihnen zu eigenen Interpretationen inspirieren liess, spielt auf "The Being Inn" mit Jan Roder und Kay Lübke ihr eigenes Material. Das zentrale Stück ist die 18-minütige "Willisau Suite", die sie mit mehreren kurzen Tracks und kürzesten Interludes ergänzt. Die "Willisau Suite" basiert auf ihren Eindrücken anlässlich eines Atelier-Aufenthaltes 2012 im Städtchen, den langen Spaziergängen in der Natur der Umgebung und den Höreindrücken aus Niklaus Troxlers Willisau-Jazz-Archiv. Alle drei Musiker exponieren sich im Verlauf des Stücks mit solistischen Interventionen, die an nicht vorhersehbaren Stellen aus dem Interplay erwachsen. Dabei läuft das Fliessgleichgewicht des Trios nie aus dem Ruder, sondern macht über Stock und Stein die unterschiedlichsten Wandlungen durch. Eberhard hat einen klaren und pointierten Sound, den sie fantasievoll in melodischen Linien zirkulieren lassen oder rabiat zuspitzen kann. Roder und Lübke gefallen mit ihrer Wendigkeit und Prägnanz. Das Trio spielt seit über zehn Jahren zusammen. Diese Vertrautheit der Musiker miteinander hält ihr Interplay elastisch und ermöglicht es, dass auch in den kargeren Zonen der Energiefunke springt.