441: ARUÁN ORTIZ. Créole Renaissance - Piano Solo

Intakt Recording #441 / 2025

Aruán Ortiz: Piano

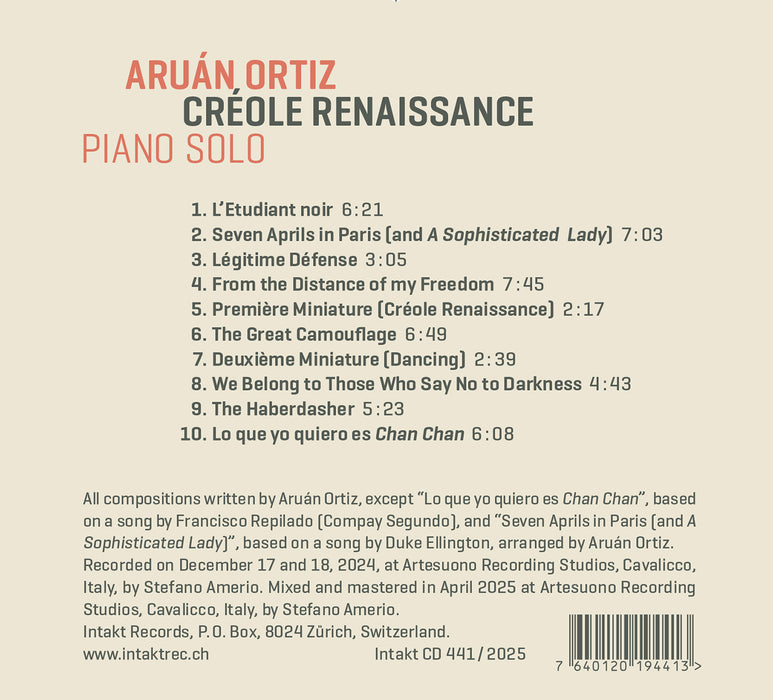

Recorded on DeceMber 17 and 18, 2024, at Artesuono Recording Studios, Cavalicco, Italy, by Stefano Amerio.

More Info

Aruán Ortiz, celebrated piano cubist, distinguished jazz improviser, award-winning composer and idiosyncratic stylist, presents Créole Renaissance, his second solo piano album on Intakt Records which comes eight years after Cub(an)ism. "Ortiz is renowned for his prodigious technique, and multiple lineages converge in his hands, from Schoenberg, Messiaen, and Ligeti to Bebo Valdés, Don Pullen, and Cecil Taylor", writes Brent Hayes Edwards and adds "Aruán Ortiz’s stunning pianistic reflections on the implications of a Créole Renaissance start here, placing the music within a long history of collective Black study. Ortiz explains that he was inspired above all by the ways Négritude poets such as Aimé and Suzanne Césaire and René Ménil deployed 'surrealist techniques to shape a new kind of narrative of Afro-diasporic life and history in the Caribbean.' If Ortiz’s music is adamantly innovative and forward-looking, in other words, it reminds us of its deep roots in traditions of Black experimentation." Créole Renaissance combines intellectual depth, emotionality and creativity to create a fascinating musical statement.

Album Credits

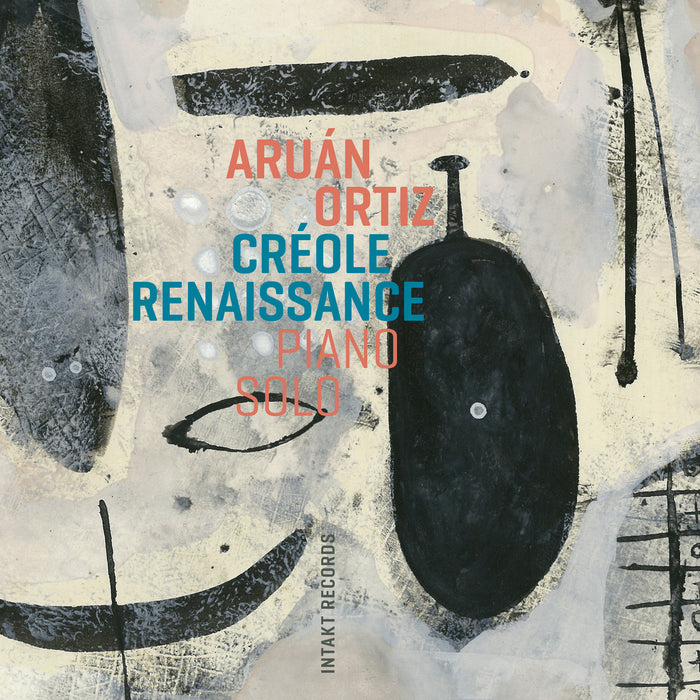

Cover art: Julio Girona (Manzanillo, Cuba)

Graphic design: Jonas Schoder

Liner notes: Brent Hayes Edwards

Photo: Mario Sabbatani

All compositions written by Aruán Ortiz, except "Lo que yo quiero es Chan Chan", based on a song by Francisco Repilado (Compay Segundo), and "Seven Aprils in Paris (and A Sophisticated Lady)", based on a song by Duke Ellington, arranged by Aruán Ortiz. Recorded on December 17 and 18, 2024, at Artesuono Recording Studios, Cavalicco, Italy, by Stefano Amerio. Mixed and mastered in April 2025 at Artesuono Recording Studios, Cavalicco, Italy, by Stefano Amerio. Cover art: Julio Girona (Manzanillo, Cuba). Produced by Aruán Ortiz and Intakt Records. Executive producer: Florian Keller. Published by Intakt Records, P. O. Box, 8024 Zürich, Switzerland.

Aruán Ortiz

Créole Renaissance

Intakt CD441 (CD, DL) ★★★★ EDITOR'S CHOICE

Aruán Ortiz (p).

Despite the malign efforts of a hostile US state department and, some would say, its own government, the small nation of Cuba continues to produce a steady stream of world-class athletes, artists and musicians - outstanding pianists in particular. Aruán Ortiz is one such: native to Santiago De Cuba but now resident in Brooklyn, he's established a formidable reputation as a performer and composer equally at home with the diverse traditions of jazz, Afro-Cuban music, and the European avant-garde.

This, his second solo recording (released on 28 August), evokes the spirits of Schoenberg, Messiaen, and Ligeti as much as Bebo Valdés, Don Pullen, or Cecil Taylor. It's a stimulating rather than an easy listen: eschewing regular tempo, conventional harmony and easily digestible melody, Ortiz deploys his formidable technique across every part of the piano, alternating deep bass thumps with frantic tone clusters on 'L'Etudiant Noir', strumming and plucking the strings on 'We Belong Too Those Who Say No To Darkness', dropping plangent dissonances into a well of silence on the Morton Feldman-esque 'The Great Camouflage'.

Only on 'Lo Que Yo Quiero Es Chan Chan', written in tribute to the famous tune by Compay Segundo, is there any overt reference to the Afro-Cuban tradition. Instead, as both the title and the spoken word interlude of 'From The Distance Of My Freedom' suggest, Ortiz is inspired by the tradition of black diasporic experimentation exemplified by the mid-20th century Négritude movement. A challenging, intellectually rigorous but rewarding listen from a major artist.

Der kubanische Pianist Ortiz ist ein he rausragender Virtuose. Wichtiger noch er verbindet disparate Welten Schönberg, Messiaen und Ligeti bis hin zu Bebo Valdés, Don Pullen und Cecil Taylor. Seine Inspiration beschreibt Ortiz als „eine eklektische Mischung, die in der Avantgarde-Musik des 20. Jahrhunderts wurzelt, aber auch von mündlichen Überlieferungen meiner afrokubanischen Wurzeln geprägt ist". Deutlich zu hören in Fragmenten aus „Sophisticated Lady" von Duke Ellington in „Seven Aprils in Paris ..." bis hin zu Anklänge an Compay Segundos mitreißendes „Chan Chan", das Ortiz in „Lo Que Yo Quiero Es Chan Chan" verwandelt. Weitere Einflüsse werden in „We Belong to Those Who Say No to Darkness" offenbar. Hier traktiert Ortiz das Piano mit nasalen Schlägen und etwas Altmetall, um an die Klangverwandtschaft mit Zither, Shekere, Oud, E-Gitarre oder dem Gamelan Celempung zu erinnern. Der Song-Titel verweist auf Aime Césares trotziges Vorwort zu „Tropiques". Césare insistierte 1941, dass, obwohl „Schatten" des Imperialismus überall in unser Leben einzudringen scheinen, wir dennoch „zu denen gehören, die Nein zum Schatten sagen. Wir wissen, dass die Rettung der Welt auch von uns abhängt."

THIS is solo piano at its most intense, inventive and beautiful. Aruan Ortiz, born in Santiago de Cuba in 1973, pays particular homage to the Martinican poet and Communist member of the French National Assembly Aime Cesaire’s student days in Paris in his new album Creole Renaissance, employing “surrealist techniques to shape a new kind of narrative of Afro-diasporic life and history in the Caribbean.”

Melody infused with wayward improvisation, introspection with musical activism, distance with proximity, and history with now-times: tracks like the spoken-word From The Distance Of My Freedom or The Great Camouflage reveal all the white masks falling away in Ortiz’s insurgent notes.

Ortiz writes of his “creative journey reconnecting my artistic vision with the layered complexity of my cultural background as a Cuban artist working across continents.” Just hear his defiant pianism through We Belong To Those Who Say No To Darkness. It challenges these racist, populist times to new assertive ways of freedom.

https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/jazz-album-reviews-chris-searle-october-10-20255

Aruán Ortiz: „Créole Renaissance“ – Vieldeutige Gestalten

Aruán Ortiz’ gedankenreiches Klavier-Solo-Album „Créole Renaissance“.

Die Renaissance trennte das sogenannte Mittelalter von der sogenannten Neuzeit und dauerte, je nach Region, an die drei Jahrhunderte. Sie wurde erst rückblickend so genannt und mit dem ebenso rückblickenden Etikett einer Neubelebung griechischer und römischer Antike aufgeladen. Diese Renaissance blieb nicht die einzige. Nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg, also vor gut einem Jahrhundert, entstand in New York die sogenannte Harlem Renaissance, getragen von Zugewanderten aus dem ländlichen Süden der Vereinigten Staaten und inhaltlich geprägt von schwarzen Künstlern, Künstlerinnen und Intellektuellen.

Und nun spielt der afro-cubanische Pianist Aruán Ortiz mit dem Gedanken an eine kreolische Renaissance. Er spielt diesen Gedanken ausführlich durch auf seinem Klavier-Solo-Album „Créole Renaissance“. Wer allerdings bei dem Etikett „afrokubanisch“ an rhythmisch pulsenden Mainstream Jazz denkt, liegt, um das gleich zu sagen, daneben.

Alles Kreolische ist Ergebnis von Imperialismus. Das Wort kommt aus dem Portugiesischen oder dem Spanischen und umschreibt ursprünglich Bevölkerungen, die in Kolonien aus der Verbindung von Menschen unterschiedlicher ethnischer Herkünfte entstanden.

Ortiz’ Album beginnt mit der Komposition „L’étudiant noir“. Das war der Titel einer einflussreichen Zeitschrift, die 1935 in Paris von schwarzen Intellektuellen gegründet wurde und beredtes Publikationsorgan einer kulturellen schwarzen Selbstbehauptung war. In Ortiz’ Komposition scheinen von überall her Fäden zusammenzulaufen. Die komplette Klaviatur wird von unten bis oben genutzt, ohne dass da etwas konsistent zu einem Stil zusammenfände. Denn es geht nicht etwa um eine nostalgische African-Roots-Feier. Es geht vielmehr um eine musikalisch gestaltete Reflexion kultureller Übergänge, Hohlräume, Beschädigungen, Überlagerungen, Brechungen, die in der Diaspora zwangsläufig entstanden sind und hinter die niemand zurückkann.

Musik, die die Schatten überwinden will

Ortiz’ Musik ist nicht nur von afroamerikanischen Musikern wie Duke Ellington, Art Tatum oder Cecil Taylor beeinflusst, sondern auch von Arnold Schönberg, Olivier Messiaen und György Ligeti. Das Kreolische ist immer Ergebnis einer Vermischung, einer neu entstandenen Komplexität, einer unbekannten Art der Artikulation. Nichts strömt hier einfach so dahin. Jeder Anschlag, jeder Ton erscheint als Ergebnis einer Veränderung oder einer Reflexion.

Auf die Spitze getrieben wird diese gedankenreiche Arbeit am Klavier in dem Stück „We Belong to Those Who Say No To Darkness“. Ortiz hat dafür das Klavier sorgsam präpariert, so dass kein Ton erklingt, der nicht an ein anderes Saiteninstrument erinnerte, an Zither, Oud, Gitarre. So erhält die Idee einer Vermischung kultureller Ausdrucksweisen eine irisierende Gestalt, die sich von jeglicher Eindeutigkeit und Identität verabschiedet hat. Die sich dabei vielleicht nicht mit dem Imperialismus versöhnt, der zu dieser Art von kreolischem Paradigma geführt hat, die aber die Schatten überwinden will, die Kolonialismus und Imperialismus auf das Leben geworfen haben.

Der einzige Musiker, den Ortiz auf seinem Soloalbum namhaft macht, ist Edward Kennedy „Duke“ Ellington, der wohl bedeutendste musikalische Vertreter der Harlem Renaissance. Der Titel des zweiten Stücks auf dem Album verweist auf Ellingtons „Sophisticated Lady“ und zugleich („Seven Aprils in Paris“) auf Zeitschriften wie „L’Étudiant noir“ oder „Légitime Défense“ oder „Tropiques“, die in der Pariser Diaspora immer nur für ein paar Jahre erschienen.

https://www.fr.de/kultur/musik/der-afro-cubanische-pianist-arua-ortiz-und-sein-gedankenreiches-klavier-solo-album-creole-renaissance-vieldeutige-gestalten-93961062.htmll

Aruán Ortiz, il pianoforte come memoria spezzata

Qualcosa di implacabile attraversa la musica di Aruán Ortiz, come se ogni gesto sulla tastiera fosse chiamato a rispondere a una storia troppo lunga per essere dimenticata, troppo dolorosa per essere elusa. Con Créole Renaissance, secondo album solista dopo Cub(an)ism, il pianista cubano residente a New York affronta non tanto il pianoforte quanto il peso stratificato delle eredità coloniali, delle genealogie nere, della memoria diasporica. Lo fa nella lingua che gli è più propria: un pianismo frantumato e febbrile, denso di silenzi e abissi, dove l’improvvisazione non è mai mero esercizio di libertà ma un modo di scavare, scomporre, riattraversare.

Registrato in due giorni intensi a fine 2024, l’album si nutre dei fantasmi e delle energie della Négritude: Aimé e Suzanne Césaire, René Ménil, le voci poetiche che seppero usare surrealismo e immaginazione come armi contro l’oblio. Ortiz ne assorbe lo spirito: le sue miniature pianistiche sono interrogazioni più che affermazioni, aperture e ferite.

In L’Étudiant Noir il contrasto tra registri acuti e profondi si fa corpo sonoro di un risveglio della coscienza, mentre Légitime Défense si agita come un campo di battaglia interiore. Altrove emergono squarci impressionistici: Seven Aprils in Paris si nutre di ombre e frammenti di Ellington (Sophisticated Lady), evocati e subito dissolti come presenze lontane. The Haberdasher pare un appunto monodico monkiano, isolato e pungente, mentre The Great Camouflage è un’oscura meditazione sul silenzio e sulla sospensione, un cammino tra note rade che diventano pensiero.

Le due Miniatures offrono un contrasto: la prima, scattante e volatile, attraversa la tastiera con nervosa leggerezza; la seconda si radica invece in accordi poderosi, quasi rituali. Nel cuore dell’album, We Belong to Those Who Say No to Darkness rompe i confini del pianoforte con corde piegate, percosse, pizzicate, prolungando l’eco delle avanguardie afroamericane da Cecil Taylor in poi. E nell’ultima pagina, Lo Que Yo Quiero Es Chan Chan, il celebre tema di Compay Segundo è riconosciuto e insieme smembrato, rallentato, fatto deragliare: memoria cubana filtrata attraverso malinconia e resistenza.

Se Cub(an)ism era stato un manifesto di geometrie astratte e rigorose, Créole Renaissance scava più in profondità, nella materia viva della memoria e nella fragilità della sopravvivenza. È un disco difficile, persino ostile, che non chiede complicità ma attenzione. Ortiz non offre conforto, pone domande. Chi siamo di fronte a queste storie di colonizzazione e sradicamento? Quale lingua resta possibile dopo la frattura?

Il suo pianoforte, attraversato tanto da Schoenberg e Ligeti quanto da Bebo Valdés e Don Pullen, diventa terreno di collisione e rinascita. Non c’è celebrazione in questa “rinascita creola”: c’è piuttosto un’urgenza, la necessità di trasformare la memoria in suono, l’assenza in presenza, la diaspora in linguaggio. In un’epoca che dimentica in fretta, Ortiz ci costringe a ricordare.

Créole Renaissance non è soltanto un grande album di piano solo, è una prova di resistenza, un atto politico e poetico insieme. E, soprattutto, è musica che non concede scampo: ci chiama a un ascolto radicale, totale, come pochi sanno fare oggi.

https://offtopicmagazine.net/2025/09/29/aruan-ortiz-creole-renaissance/

Pianist, violist and composer Aruán Ortiz, originally from Santiago de Cuba, now lives in Brooklyn, where he has been an active musician in the progressive jazz and avant-garde scene for over 15 years. He has been called “one of the most creative and original composers in the world,” and has written music for ensembles, orchestras, dance companies, chamber groups and feature films, incorporating influences from contemporary classical music, Cuban and Haitian rhythms and avant-garde improvisation.

He consistently strives to push stylistic musical boundaries, and since coming to the United States has performed, toured, and recorded with musicians such as Wadada Leo Smith, Don Byron, Greg Osby, Wallace Roney, Nicole Mitchell, Cameron Brown, Michael Formanek, William Parker, Adam Rudolph, Andrew Cyrille, Henry Grimes, Marshall Allen, Hamiet Bluiett, Oliver Lake, Rufus Reid, Graham Haynes, Terri Lyne Carrington, and Nasheet Waits. He has also collaborated with choreographers José Mateo, Danis Mora, and Milena Zullo; filmmakers Ben Chace, Mariona Lloreta, and Mónica Rovira; poets Abiodun Oyewole of The Last Poets; writer/poet/filmmaker Mtume Gant; DJ Logic, and Val Jeanty Inc.; and acclaimed German authors Angelika Hentschel and Anna Breitenbach.

Here at Voss he is almost considered "one of us" after collaborating with vocalist Grete Skarpeid on a couple of releases, and for his participation in her memorial concert, together with vibraphonist Rob Waring, vocalist Berit Opheim and the choir d'kor at Vossa Jazz in 2024. He has released a number of albums on Intakt Records, and in 2017 he made the solo release Cub[an]ism.

Now he is out again with a solo album recorded at Artesuono Recording Studios in Cavaicco, Italy on December 17 and 18, 2024. Here we get, mainly, his own compositions, but he also does Duke Ellington's "Seven Aprils in Paris (and A Sophisticated Lady)" and "Lo que yo quiero en Chan Chan" based on a composition by Francisco Rapilado (Compay Segundo).

Ortiz is a creative and brilliant pianist, who in these 10 compositions/improvisations almost serves a holistic work, which starts "openly" and exciting in "L'Etudiant moir", where he shows himself as a thoughtful and extremely creative pianist. This is a political "message" with a look back at a political, international group of students in Paris in 1935. And from here on out, this is a release where he addresses and honors several political, strong groups, especially within the Creole part of the world, where he has his history.

And adding Duke Ellington between these fits perfectly. And his version of "Seven Aprils in Paris (and A Sophisticated Lady)", are two excellently performed songs that are connected here to a joy of ballad performance.

Ortiz is a master at interpreting ideas and historical events, while at the same time, with his distinctive, and relatively free playing, he can (almost) be compared to Keith Jarrett in his solo playing. But I think he is much freer than Jarrett, and occasionally comes close to freer pianists, such as Cecil Taylor. But he is a personal pianist who also verbally tells about the events he plays, as in the fine "From the Distance of my Freedom".

All the way through he has made a record that you are almost "glued to your chair" to take in all the details of the fine playing. And when he makes a song titled "We Belong to Those Who Say No to Darkness", you know that he is not one of Trump's favorite musicians.

All the way through there is the understandable, melancholic tone of what he performs. It is lyrical, beautiful, thoughtful and you can hear that it pains Ortiz to think back to the history his people have lived through. There is a lot of history between the notes here, which we in the Nordic countries have not learned much about in history classes at school.

And I would rather listen to Ortiz solo for 100 days than five minutes of the American president's nonsense. Because this is creative art at a very high level. You just have to sit back and enjoy, even if his stories touch us deep into the soul.

https://salt-peanuts.eu/record/aruan-ortiz-2/

Créole Renaissance is pianist Aruán Ortiz’ seventh release from Intakt as leader or co-leader, and his Créole Renaissance is pianist Aruán Ortiz’ seventh release from Intakt as leader or co-leader, and his second solo album for the label, coming some eight years after the brilliant Cub(an)ism. that earlier invocation of both Caribbean culture and the compound perspectives of modernism is similarly at work in this collection of pieces. It specifically celebrates the 1930s “Négritude movement” in paris, its literary periodicals and martinique-born poets (Aimé and Suzanne Césaire and rené ménil) supplying the titles for such Ortiz compositions as “L’Étudiant noir” and “Légitime Défense” (as discussed in brent Hayes edwards’ illuminating liner notes). If Cuban jazz piano frequently emphasizes the island’s historical and cultural links to the decorative flourishes of european romanticism, Ortiz is very

different: his playing can be spare or dense, but either way, it is intense, percussive and mercurially alert to rhythmic possibility. Its roots reach to ellington, directly referenced in the title of “Seven Aprils in paris and A Sophisticated Lady”, but there are also affinities with pianists Don pullen and Andrew Hill. the nine tracks range from taut miniatures to more expansive visions. the two-minute “première miniature” consists of rapid ascending phrases growing ever more exuberant and complex. “Deuxieme miniature (Dancing)”, only slightly longer, moves more characteristically up and down, while the still brief “Légitime Défense” is a joyous explosion, close-voiced clusters running riot across the keyboard. moving to more sustained pieces, there are strangely surreal dreamscapes. “We belong to those Who Say No to Darkness” is taut drama, isolated bass tones matched to a shimmering banjo-like prepared middle register and occasional chords. “the Great Camouflage” is a somber elegy haunted by beauty, slow brooding chords and isolated tones gradually ascending the keyboard, with sometimes palpable silences or ringing harmonics that gradually

fade. the longest track, “From the Distance of my Freedom”, is a remarkable event in the history of jazz and spoken word: Ortiz speaking as well as playing the piano—part dialogue, part obligato, part solo. The text includes a few sentences, but it’s shaped by singular words and cellular phrases, many of which end in “-ism” (“primitivism versus modernism,” “surrealism,” “post-colonialism,” “neologism.”

Also repeated: “black renaissance.”) Somehow simultaneously serious and playful, the spoken component ends at the five-minute mark, giving way to the free dance of Ortiz’ piano playing. This is music of intense creativity and emotion, a commemorative dance between lament and liberation.

Le pianiste cubain de Brooklyn évoque l’émergence d’une culture africaine qui s’affirme dans l’univers européen et états-unien. On croise ici le souvenir de L’étudiant noir, éphémère journal animé par Aimé Césaire et Léopold Senghor au milieu des années trente, et d’autres publications de même nature. Cette renaissance créole trouve aussi sa source dans le mouvement Harlem Renaissance des USA à partir des années 20, avec notamment une allusion à un thème de Duke Ellington. Un parcours musical abstrait, dans une esthétique qui convoque autant les musiques de l’avant garde européenne du vingtième siècle que les sonorités des musiques traditionnelles, et bien sûr toutes les métamorphoses musicales brassées par l’univers caribéen. Mais ici l’abstraction n’occulte pas la sensibilité sonore et musicale. Elle magnifie au contraire la pluralité de ces matériaux dans la singularité de peuples dispersés par l’histoire. Et c’est une formidable excursion dans la mémoire : pas une mémoire courte mais une mémoire longue, qui prend en compte l’essence des cultures plutôt que l’écume des mondes et des modes. À déguster avec tout le soin de l’attention et de la plongée dans la perception la plus fine. Et là le plaisir est considérable

https://lesdnj.over-blog.com/2025/09/aruan-ortiz-creole-renaissance.html

Aruan Ortiz – piano, compositions (except Lo Que Yo Quiero Es Chan Chan)

Cuban-born, Brooklyn-based pianist Aruán Ortiz has been called a “piano cubist”—a tag that makes sense once you sit with his new solo album Créole Renaissance. Instead of flowing lines or familiar harmonic paths, Ortiz works with fragments, shards, and sudden shifts, more like a Picasso sketch than a landscape painting. Eight years after his last solo release (Cub(an)ism), he’s back at the keys with music that’s as much about thought and history as it is about sound.

The inspiration is the mid-20th century Négritude movement, which was sparked in Paris by French writers influenced by the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. That earlier flowering of Black culture gave us voices like Langston Hughes and the music of Duke Ellington—both of whom lit the path for Négritude’s writers to reclaim Black identity from colonial stereotypes. Ortiz takes that same spirit of defiance and filters it through the piano. What comes out isn’t polite background music—it’s confrontational, exploratory, sometimes cryptic, always searching.

The opener, ‘L’Étudiant noir,’ is all about extremes: deep bass notes tapped like distant thunder against bright, tinkling highs that scamper across the top register. The music swells into a rolling rhythm before breaking apart again, like two currents converging but never fully merging. ‘Seven Aprils in Paris (and A Sophisticated Lady)’ draws from Ellington, though Ortiz pulls it so far inside out you only catch fleeting glimpses. It moves at a slow, almost somber pace, as if the notes are walking with heavy shoes but never quite landing on a melody.

When he does go for velocity, it’s jagged and unpredictable. ‘Légitime Défense’ sets flurries of high notes against agitated bass rumbles, the piano sounding less like a single instrument than two forces in argument. ‘From the Distance of My Freedom’ takes a different route: Ortiz speaks over the music, reflecting on colonialism, Black intellectualism, and his own artistic journey. The voice is fragile and human; the piano builds around it with flourishes that finally hint at melody.

The shorter pieces—‘Première Miniature’ and ‘Deuxième Miniature (Dancing)’—play with repetition, little cells of notes that climb, descend, collide, and cut off abruptly. ‘The Great Camouflage’ takes on a heavier weight with block chords, punctuated by delicate touches that feel like Ortiz is holding something back, testing the edges of silence.

By the time we reach ‘We Belong to Those Who Say No to Darkness,’ Ortiz has opened up the piano like a laboratory. He strokes the strings, taps out thuds that sound like other instruments, and mixes it with bright, almost hymn-like figures on the keys. It’s eerie, inventive, and completely of a piece with the defiant line Césaire once wrote: “we belong to those who say no to the shadow.”

The album closes with ‘Lo Que Yo Quiero Es Chan Chan,’ Ortiz’s abstract take on Compay Segundo. He starts with resonant bass notes and scattered phrases, then lets the music gather steam—short, roaming bursts that almost stumble into melody before dissolving into quiet again. It feels less like a cover than a dream about the song, refracted through Ortiz’s restless imagination.

Ortiz has always thrived at intersections—Afro-Cuban roots, avant-garde composition, free improvisation—and Créole Renaissance might be his most personal crossroads yet. The album isn’t easy listening; it’s a series of confrontations with history, culture, and sound itself. But it rewards patience. Like the poets of Négritude, Ortiz shows us identity in fragments—sometimes harsh, sometimes delicate, always alive.

https://jazzviews.net/aruan-ortiz-creole-renaissance-piano-solo/

In seinen Projekten verschmilzt der aus Santiago de Cuba stammende Pianist und Komponist Aruán Ortiz Einflüsse aus der zeitgenössischen klassischen Musik, dem Avantgarde Jazz mit Folklore seiner Heimat und der Magie afro-karibischer Rhythmen. Neben seinen eigenen Gruppen wirkt er im Quartett des Saxofonisten James Brandon Lewis mit. Vor rund acht Jahren erhielt „Cub(an)ism“ die höchste Bewertung beim Down Beat Magazin. Auf seinem zweiten Solo-Album "Créole Renaissance" reflektiert Aruán Ortiz die Geschichte der Négritude - einer Mitte der Dreißigerjahre gegründeten antikolonialen, politischen und kulturellen Bewegung - in seiner Musik. Das Eindringen in dunkle Klangwelten und die Entdeckung geheimnisvoller Motive lotet Ortiz in "L'Etudiant Noir" mit tiefen Tönen aus. In "Légitime Défense" erzielt der Pianist mit granithaften Tonfiguren und melodischen Clustern eine enorme Klangfülle. Mit strukturierten Improvisationen definiert er in "Lo Que Yo Quiero Es Chan Chan", einem bekannten Song des kubanischen Sänger Compay Segundo vom Buena Vista Social Club, die Kunst der Abstraktion. Superb!