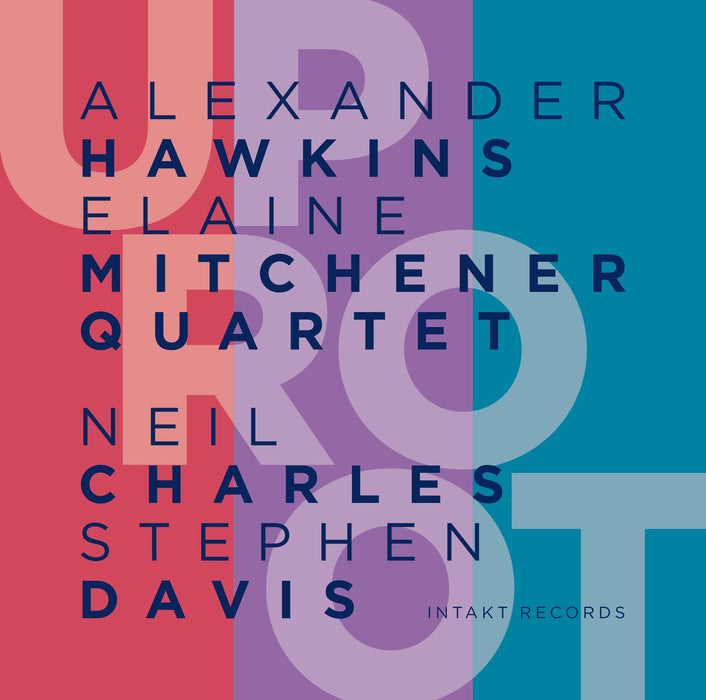

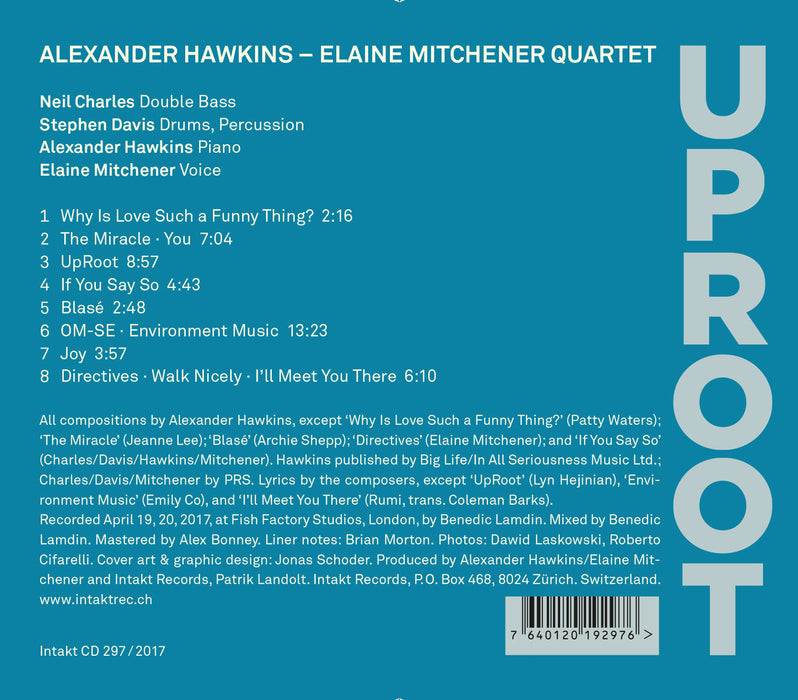

297: ALEXANDER HAWKINS – ELAINE MITCHENER – QUARTET. Uproot

Intakt Recording #297/ 2017

Neil Charles: Double Bass

Stephen Davis: Drums, Percussion

Alexander Hawkins: Piano

Elaine Mitchener: Voice

Recorded April 19, 20, 2017, at Fish Factory Studios, London.

More Info

This quartet represents the collaboration of two of the most distinctive voices of their generation, and stakes out a remarkable common ground from the pair’s vast range of influences and experience. The repertoire fuses Elaine Mitchener’s unique way with both melody and abstraction, with Alexander Hawkins’ idiosyncratic compositional and pianistic world; as well as spotlighting reimaginings of a small number of beautiful Jazz tunes which reveal the influence of precursors such as Jeanne Lee and Archie Shepp. Structurally, the group with Neil Charles on bass and Stephen Davis on drums function as complete equals, veering radically from the traditional norm of ‘singer plus rhythm section’, instead treating this as only one possible dynamic amongst many.

Brian Morton writes in the liner notes: „This is music that speaks directly to our condition, our uprootedness and our strange fixities of purpose alike. It is clever and emotional. It comes out of jazz, and a whole lot else besides. Here is a group, populated by some of our most singular and precious talents, whose greatest talent is to communicate, and whose music already bears the signs of maturity and longevity

Album Credits

Cover art and graphic design: Jonas Schoder

Liner notes: Brian Morton

Photos: Dawid Laskowski, Roberto Cifarelli

All compositions by Alexander Hawkins, except ‘Why Is Love Such a Funny Thing’ (Patty Waters); ‘The Miracle’ (Jeanne Lee); ‘Blasé’ (Archie Shepp); ‘Directives’ (Elaine Mitchener);and ‘If You Say So’ (Charles/ Davis/Hawkins/Mitchener). Recorded April 19, 20, 2017, at Fish Factory Studios, London, by Benedic Lamdin. Mixed by Benedic Lamdin. Mastered by Alex Bonney. Produced by Alexander Hawkins/Elaine Mitchener and Intakt Records, Patrik Landolt.

ELAINE MITCHENER is a singer who defies all categories — and that’s the way she likes it, she tells Chris Searle

AT SCHOOL in Tower Hamlets in east London, Elaine Mitchener’s flute teacher was a jazz and free-improvising musician who introduced her to the greats — from musicians Charlie Parker to John Coltrane, vocalists from Billie Holiday to Janet Baker and composers such as Bela Bartok and Karlheinz Stockhausen.

Thus her inspiration, she stresses, is “environmental. I am definitely not a jazz singer.” As well as a vocalist, she’s a movement artist and composer who's been described the Finanacial Times as a “genre-crossing virtuoso.”

When she was making her compelling album Uproot with pianist Alex Hawkins, double bassist Neil Charles and drummer Stephen Davis, she told Hawkins that she’d only sing in a quartet if her voice was regarded as an instrument. He understood.

“I’m not interested in vocalist plus trio,” she says. “Uproot describes destabilising energy, interrogating conceptions of what an experimental jazz quartet ought to sound like.”

Growing up in a Jamaica-rooted and music-loving family, she was brought up on “a heavy dose” of ska, reggae and dub from her father.

“Both my parents sang,” she says. “Dad played guitar — and clarinet, kind of! — and my elder brother seemed to play every instrument of the orchestra, courtesy of the much-missed free instrumental lesson scheme of the Inner London Education Authority (ILEA).

“I followed on, playing recorder, piano, flute and French horn at secondary school, again thanks to ILEA.”

Mitchener honed her craft at the Seventh Day Adventist church she attended from the age of 11, where she was exposed to gospel music.

“To watch young people like myself play and sing with such incredible musicality and maturity was truly inspiring,” she recalls.

“Musicians I worked with then have since become professional and have lucrative careers.”

She sees herself as part of a black British-Caribbean cultural tradition which “acknowledges, respects and reveres great Caribbean writers and musicians, while also celebrating the unique culture born from being a black African-Caribbean woman and all that brings with it.”

Musical activism is important to her and choosing songs which have strong messages which distinguish them from being mere entertainment. “I’m not against entertainment but my interests lie elsewhere. We need to think and act to create change,” she says.

It’s in this spirit that her upcoming concert at Kings Place in London on June 14 is dedicated to the late US singer Jeanne Lee. “She used her voice for activism,” Mitchener declares, “and by doing this she eschewed and defied categorisation, treating her voice instrumentally. Nothing was superfluous with her, every vocal sound and gesture mattered and was totally committed.”

She remembers as a teenager being given a cassette of her record The Newest Sound Around, with pianist Ran Blake: “I didn’t know what to make of it at first. Their dissonant, experimental approach to interpreting jazz standards unnerved me and I wasn’t sure I liked her voice or what they were doing. I had to wait until my musicality and sensibilities matured.”

At Kings Place, Mitchener will be playing with some marvellous musicians — cellist Anton Lukoszevieze and saxophonist Jason Yarde as well as Hawkins, Charles and drummer Mark Sanders at the concert.

“I am honoured and extremely proud to be working with such titans,” she says. “Their enthusiasm and energy is incredible. And if someone feels encouraged and more positive as a result of hearing us, then that is all we can ever hope for.”

https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/c/i-am-definitely-not-jazz-singer

Eure Queen ist ein Reptil

Was tun, wenn der Brexit kommt? Ein Streifzug durch Großbritanniens brodelnde Jazz-Szene

Aus der britischen Publikumspresse erfuhr man lange wenig über die britische Jazzszene. Wer sich informieren oder die neusten Veröffentlichungen hören wollte, musste auf Fachzeitschrifien oder spezialisierte Radiosendungen ausweichen. In den vergangenen anderthalb Jahren ist es nun einigen Musikern gelungen, aus diesem Mediengherro auszubrechen und in die Sonntagszeitungen und Hauptsendezeiten vorzudringen. Der britische Jazz ist plötzlich ein Thema.

Europäische und amerikanische Veranstalter sehen das auch so. Von Sardinien bis Skandinavien buchen Festivals britische Improvisatoren. Letzten Januar präsentierte das Winter Jazzfest in New York einige viel beachtete junge Künstler aus dem Vereinigten Königreich: die Saxofonistin Nubya Garcia, die Trompeterin Yazz Ahmed und die Gruppe The Comet Is Coming des Saxofonisten Shabaka Hutchings.

Hutchings steht im Mittelpunkt der aktuellen Aufregung, weil er so aktiv ist. Da gibt es Shabaka & The Ancestors mit südafrikanischen Musikern und Sons of Kemet, ein hochenergetisches, rein britisch besetztes Quartert, das seit fast einem Jahrzehnt zusammenspielt; es ist sein erfolgreichstes Projekt.

Der Titel des jüngsten Albums der Band, Your Queen Is a Reptile, mag Hutchings Lust an der politischen Provokation widerspiegeln, doch ist es zuallererst die Musik, die mit ihrer scharfsinnigen Neufassung zentraler Elemente der Jazzgeschichte und des karibischen Folks die Fantasie beflügelt. Mit einer Tuba und zwei Schlagzeugen neben Hutchings Tenor saxofon haben die Sons of Kemet einen rauen, nervösen, polyrhythmisch aufgeladenen Klang, der auf der Bühne explodiert. Ihr bassbetontes Grollen trifft den Nerv eines jüngeren Publikums, das mit Hip-Hop, Dub und Tanzmusik groß geworden ist, aber auch den älterer Hörer, die den abstrakten Avantgarde-Charakter schätzen. Was der 35-jährige Londoner zudem vermittelt, ist ein ausgemachter Stolz auf seine barbadischen Wurzeln – ein Stolz, den er bei vielen seiner afrokaribischen Kollegen beobachtet. >>Wir sagen: Das ist unsere Vision der Musik.<<

Schwarze wie weiße Musiker experimentieren mit einem breiten Spektrum an Material. Der Schlagzeuger Moses Boyd erforscht in seinem Exodus-Projekt die kubanische Tradition der Batá-Trommel (siehe auch nächste Seite), während die Pianistin Sarah Tandy Swing und Reggae packend verbindet. Die Saxofonistin Camilla George, auf nigerianische und grenadische Wurzeln zurückblickend, verschmilzt Calypso, Highlife und Soul in ihrer Musik. Darüber hinaus ist sie von den Yoruba-Parabeln inspiriert, die sie in ihrer Kindheit zu hören bekam.

>>Die Aufmerksamkeit, die meiner Musik im vergangenen Jahr entgegengebracht wurde, ist gewaltig<<, sagt dic 29-jährige George. Wie Hutchings und zahllose andere hat sie von den >>Tomorrow's Warriors<<-Workshops profitiert, die der Bassveteran Gary Crosby seit Mitte der Neunzigerjahre veranstalter.

London ist nicht der einzige Ort, an dem im britischen Jazz interessante Dinge geschehen. Hutchings verbrachte die ersten Jahre seiner Karriere in Birmingham, wo er mit dem Saxofonisten und Rapper Soweto Kinch zusammenarbeitere. Bezeichnend ist es, dass mit Xhosa Cole ein weiterer Saxofonist aus Birmingham jüngster Gewinner des prestigeträchtigen BBC Young Jazz Musician of the Year Award ist. Bristol, Cardiff, Glasgow, Leeds und Manchester haben über die Jahre viele große Talente hervorgebracht; auch Newcastle ist ein pulsierender Standort kreativer Musiker. Die Saxofonistin Faye MacCalrnan zählt dazu. Sie hat ihre eigenen Bands, biklet zudem mit dem Bassisten John Pope und dem Schlagzeuger Christian Alderson das gemeinschaftliche Trio Archipelago. Dessen metamorphotischer Sound bewegt sich stimmig zwischen knackigen, kraftvollen Riffs und introspektiven Ambientpassagen, die durch geisterhafte Elektronik und abrupte, schroffe Verzerrungen erweitert werden.

MacCalman führt diesen Eklektizismus auf ihre Umgebung zurück. >>Die Verbundenheit zwischen den Musik- und Kunstszenen in Newcastle führt zu jeder Menge Cross-over zwischen Genres wie Folk, Rock, Jazz und freier Improvisation, was auch in die Jazzszene einfließt und sie sehr fortschrittlich macht. Vor ein paar Jahren entstand das Newcastle Festival of Jazz and Improvised Music, das jeden Oktober unglaubliche Musik in die Stadt bringt. Sie reicht von halbimprovisierter Stummfilm-Musik, die Geschichten erzählt, bis hin zu einer Free-Jazz-Legende wie Joe McPhee.<<

Der verehrte Amerikaner McPhee arbeitet viel in Europa, und wenn es einen gemeinsamen Nenner zwischen den jungen Jazzmusikern in Nord- und in Südengland gibt, dann ist es die Bedeutung, die der Kontinent als Markt wie als Ort des Austausches mit anderen Künstlern hat. Was natürlich bedeutet, dass Faye MacCalman den Brexit ansprechen muss – obwohl viele Briten das Wort aufgrund schierer emotionaler Erschöpfung nicht mehr in den Mund nehmen wollen.

...

Patty Waters et Jeanne pour débuter cet Lee enregistrement on a trouvé plus idiot, reconnaissons-le. Pleine voix pour Why Is Love Such a Funny Time; feulements, écartèlements, cris pour The Miracle on découvre ici Elaine Mitchener, vocaliste aux mille possibles. Dans des cadres plus improvisés et plus périlleux, la chanteuse porte le borborygme haut et le babil bas, et ce, sans jamais monopoliser l'espace.

Alexander Hawkins milite pour que s'étende l'harmonie jusqu'aux ruptures. Il est certes moins extravagant qu'en duo avec Evan Parker mais, ce terrain, légèrement plus suave, lui va à merveille. Et quand Elaine prend le parti des duos (Neil Charles puis Stephen Davis), peut alors se confirmer la singularité de cette étonnante musique. Idem quand un jazz chromatiquement malade se libère: Elaine Mitchener est un pur diamant, une découverte sérieuse et enthousiasmante. Vite, la suite..

Why Is Love Such a Funny Thing, heißt es zu Beginn. Ein Song von Patty Waters eröffnet den Silberling, den Pianist Alexander Hawkins mit der Sängerin Elaine Mitchener, dem Bassisten Neil Charles und Drummer Stephen Davis eingespielt hat. Die Frage bleibt zwar weitgehend unbeantwortet, aber die Musik überzeugt ziemlich. Diese stammt weitgehend von Hawkins, eine Nummer von Jeanne Lee, The Miracle, und eine von Archie Shepp, Blase, in einer knapp dreiminütigen Version. Klingt eigentlich ganz klassisch nach einem Piano- trio, das eine Vokalistin begleitet, stimmt aber da nicht. Die vier arbeiten auf Augenhöhe. Das klingt sehr fein verwoben, wechselt hübsch zwischen fast traditionellem Songwritertum und freier Impro, spielt klug mit Verdichtung und Entflechtung, mit feinsinniger Tempodifferenzierung, mal geruhsam, mal forciert. Jeanne Lee scheint mit Elaine Mitchener seelenverwandt. Das veranlasst, wieder einmal das wunderbare After Hours-Album von Lee im Duo mit Mal Waldron hervorzukramen. Das ist auch schon 25 Jahre alt. Und dann klingt auf der Platte mit Track #6, OM-SE Environment Music, wieder ganz etwas Anderes. Großartiger, abwechslungsreicher Tonträger.

Elaine Mitchener e il suono della paura

Dalla classica al jazz passando alla contemporanea, è il lungo percorso dell’eclettica artista londinese. Il suo progetto - «Sweet Tooth», racconta i drammi del sistema della schiavitù e della tortura. «Ho registrato l’esperienza di milioni di persone: la privazione della libertà, la vendita all’asta, la lavorazione della canna per produrre zucchero»

Elaine Mitchener è una giovane vocalist britannica i cui interessi spaziano dal jazz alla musica contemporanea, dall’improvvisazione alla performance, dal movimento alla danza. Ha in repertorio i Song Books di John Cage. Ha interpretato Manga Scroll di Christian Marclay, oggi forse più conosciuto nell’ambito dell’arte contemporanea che della musica, e lavori del compositore sperimentale Alvin Lucier e di Ben Patterson, uno dei protagonisti di Fluxus. Il suo Sweet Tooth, che ha avuto la sua prima londinese nel febbraio 2018, è una vibrante riflessione in chiave di teatro musicale sulla schiavitù a partire dalle sue origini giamaicane. Ha allestito un programma di Vocal Classics of the Black Avant-Garde, con brani di Jenne Lee, Archie Shepp, Joseph Jarman, Eric Dolphy (lo riproporrà domani a Londra al Café Oto). Sta preparando un omaggio a Jeanne Lee, la più grande vocalist del free (prima il 14 giugno nella capitale britannica, al Kings Place). E con il pianista Alexander Hawkins, uno dei più brillanti e dinamici protagonisti della giovane generazione dell’improvvisazione europea, ha inciso in quartetto UpRoot (Intakt, 2017) intestato ad entrambi. Lo scorso settembre è stata ospite in Sardegna per il festival Ai confini del jazz, sua prima esibizione italiana.

Come ha iniziato a cantare?

Sono nata a Londra, i miei genitori sono giamaicani. Ho cominciato a cantare in chiesa, gospel, ho fatto parte di un gruppo vocale di ragazze: in questo senso il mio è stato un percorso molto tradizionale. Poi ho studiato canto al Trinity College of Music e ho preso lì il mio diploma, poi ho continuato alla Goldsmiths University. Ammiravo il canto classico, l’ho studiato alla Trinity, e ho imparato a cantare in italiano, francese, tedesco: arie, brani del repertorio tradizionale e la base di quella tecnica è veramente importante per quello che faccio adesso. Mi piace andare alle opere, mi piace sentire le cantanti, le ammiro e sono una grossa ispirazione, ma ho capito presto che non avrei voluto avere una carriera da cantante classica tradizionale perché i miei interessi sono più ampi.

Cosa le mancava?

Se da giovane hai cantato gospel in chiesa, ti sei trovata a dover eseguire delle canzoni all’ultimo momento, giusto il tempo di capire il titolo e di sperare che il pianista o l’organista la suoni in una chiave in cui puoi cantarla: e, semplicemente, lo fai. E quando hai imparato a farlo da molto giovane hai imparato ad improvvisare, e a farlo senza avere paura, ed è una cosa che ti piace oltre che un allenamento eccezionale per una attività come musicista professionista. Ho anche imparato che le canzoni aiutano le persone a guardare a se stessi, e a prendere delle decisioni importanti: una canzone può cambiarti la vita. Questo me lo ha insegnato la chiesa, non il music college. Dopo ho trovato veramente difficile sentire in questa prospettiva le arie di Mozart o di Puccini: io conosco il senso di questi brani che musicalmente sono meravigliosi, ma sono qualcosa che non è per me esperienza reale. Il music college ha un po’ ucciso il mio amore per il canto, e ne sono uscita non molto convinta.

E come è arrivata poi all’attività professionale?

Ho fatto altre cose, cantavo un po’ ma avevo paura di farla diventare una carriera, perché è dura. Cantare come lavoro mi spaventava, avevo degli amici che lo facevano e vedevo che lotta era. Hai un’ora di gioia e dopo ti dici: quando sarà la prossima performance? Quando entreranno altri soldi? Lavoravo per la Ricordi come promotion manager, promuovevo compositori a Londra, e ho appreso molto sul business della musica classica, un impiego decisamente interessante. È successo che qualcuno dei miei clienti ha scoperto che cantavo e mi hanno chiesto di farlo nei lavori dei compositori che cercavano di far eseguire. Mi hanno incoraggiata. In definitiva ero una performer: la porta si era aperta. E così ho cambiato lavoro.

Quando è entrata in contatto con la scena improvvisativa?

Avevo quattordici-quindici anni e il mio insegnante di flauto a scuola era un improvvisatore free, Neil Metcalfe. Siamo diventati amici, io ero troppo piccola per andare ai concerti, ma lui è stato il mio primo contatto con questa scena. Poi ho cominciato ad entrare in questo ambito con il mio ex marito, pianista: oltre che con Neil ho lavorato molto con Steve Beresford, Evan Parker, Mark Sanders, John Butcher, David Toop, e sono stata guest con la London Improvisers Orchestra. Amo molto lavorare con un vocalist come Phil Minton. È una scena ricca con improvvisatori di talento.

Un recensore ha scritto che grazie all’inte...

Inspired by his residency at the prestigious Civitella Ranieri in Umbria this summer, pianist Alexander Hawkins has been holed-up in Zurich, laying down his latest solo suite for the Intakt imprint. For these recordings, Hawkins has had access to the finest Steinway in Switzerland, housed in the studio of Swiss National Radio, where he teamed-up with sound engineer Martin Pearson, a doyenne of piano documentation. Pearson is well- known for his work on Cecil Taylor's The Willisau Concert and Irène Schweizer's First Choice, as well as his various collaborations with Keith Jarrett. Hawkins will be putting the finishing touches to his as-yet-unnamed album over the winter, which is scheduled for release in March 2019. "This new album documents some of the things I've been working on over the past half-decade," says Hawkins, when discussing the forthcoming record, "both with respect to concepts such as the balance of freedom and structure, and with respect to technical aspects of the piano itself." Catch him performing live as a special guest of the Emulsion Sinfonietta at the Hexagon Theatre, Birmingham on Friday 2 November and at Kings Place on Sunday 18 November, when Hawkins appears as part of Ethan Iverson's Last Rent Party during this year's London Jazz Festival.

In dit Britse kwartet worden de mogelijkheden van gesproken en gezonden woord van Elaine Mitchell uitgebouwd door de vrij opererende pianist Alexander Hawkins met bassist Neil Charles en drummer Stephen Davis. Er wordt ook spontaan geïmproviseerd, maar het meeste materiaal is geschreven door Hawkins. Stukken van Patty Waters, Archie Shepp en Jeanne Lee komen ook langs. Mitchell doet in haar musiceren inderdaad sterk denken aan Lee, al lijkt ze er qua klankkleur helemaal niet op. In een zeer korte tijd worden we een emotionele achtbaan opgestuurd, aange- zwengeld door de soms geniale invallen van Hawkins die schijnbaar willekeurig uit de jazzgeschiedenis weet te citeren, van Elmo Hope via Cecil Taylor tot nu. Het spel van Charles en Davis is vooral dienst- baar zonder alleen maar te begeleiden of aan te vullen. Het kwartet klinkt echt als een een- heid die overigens elk moment in intrigerende losse delen uiteen kan vallen. Waarschijnlijk een nieuwe standaard voor geïmproviseerde muziek met zang.

Mais d’abord un petit tour par l’Angleterre. J’avais découvert le formidable pianiste Alexander Hawkins il y a quelques années grâce à deux disques, « Song Singular » en solo et « Step Wide, Step Deep » en sextette, publiés par le label Babel (BDV 13120 et 13124). Nous le retrouvons pour la première fois chez Intakt avec un quartette qu’il codirige avec la vocaliste expérimentale, improvisatrice et performeuse théâtrale Elaine Mitchener, née à Londres de parents jamaïcains. Avec une rythmique de première force et particulièrement impliquée, Neil Charles (contrebasse) et Stephen Davis (batterie, percussions), ils proposent une série de pièces à la fois ouvertes, parfois débridées, mais rigoureusement maîtrisées, fruit probable d’une longue maturation. Lorsqu’on remarque que Elaine Mitchener a travaillé avec des gens comme Steve Beresford, George Lewis, Phil Minton, Evan Parker ou David Toop, et, qu’à côté des compositions du pianiste, les musiciens ont puisé chez Patty Waters, Jeanne Lee et Archie Shepp (Blasé, titre d’un vieil album Byg que chantait... Jeanne Lee), On aura une idée de la voie choisie par ces musiciens, et cela dans une démarche résolument contemporaine. « Uproot »

https://www.culturejazz.fr/spip.php?article3360

Sonorities Festival Belfast is one of Ireland's longest-running contemporary music festivals. This year saw the biannual SFB hit the thirty-year mark and to celebrate the milestone festival directors Miguel Ortiz and Simon Waters assembled an eclectic programme of contemporary musicians, composers and sound artists that straddled the worlds of multi-media performance, classical, contemporary string and choral, electronica, audio-visual and, with the Alexander Hawkins/Elaine Mitchener Quartet leading the way, some hardcore improvised music.

A dozen or so venues across the city welcomed artists from twenty nine countries to SFB 2018. Besides the music there were also some heavyweight talks under the umbrella of the Sonorities Symposium, spearheaded by keynote speaker Brian Kane, Yale professor and author of Sound Unseen: Acousmatic Sound in Theory and Practise (Oxford University Press, 2014).

Composer Pierre Schaeffer's term 'acousmatic sound' refers to, in a nutshell, disembodied sound. We experience acousmatic sound all the time but we don't usually associate it with a concert, precisely because we can see the creators of the sounds. However, watching the Alexander Hawkins/Elaine Mitchener Quartet—as intense a listening experience as you're likely to encounter—it was clear that you could only really focus visually on one musician at a time and therefore much of the music, arguably, was disembodied to some degree. When pianist, vocalist, bassist Neil Charles and drummer/percussionist Steve Davis were locked in harness all notes were sounds, all sounds were notes. The overall effect was a wall of pulsating sound, an ensemble sound that transcended traditional notions of individual roles.

Yes, Mitchener sang, sometimes with stunning operatic beauty, but unaccompanied for the first five minutes or so of this seventy-minute concert she worked her articulators furiously to fashion sounds more usually associated with madness, demonic possession, or children unselfconsciously playing. Comic, seductive and eerie in turn, Michener's opening salvo was punctuated by short passages of poetry and the stark contrast between these fleeting moments of seeming lucidity and the provocative stream-of-consciousness sounds either side worked an emotional effect not unlike Samuel Beckett's nerve-shredding monologue Not I.

When Hawkins, Charles and Davis entered the sonic act it propelled Mitchener to soaring vocalisations. Hawkins, at first maintaining a melodic vamp, soon ventured into wildly expressive soloing that was, with shades of Cecil Taylor, essentially rhythmic and dynamically percussive in nature. Charles and Davis meanwhile were whipping up storms of their own and the quartet's unified voice became an energizing force. Fascinating the collective changes up and down gears; Davis at his most animated, juggling sticks, brushes and percussive aids—mini-cymbals, gongs and shakers—which, having sounded, were then tossed over his shoulder, sounding again on impact.

During the music's not infrequent delicate passages Davis would place such objects on the drum skins with the delicacy of a parent laying a new-born in its cot; for all the quartet's sonic turbulence the care to avoid sounds at times, particularly during lyrical passages was equally striking. The sheet-music before all four was a reminder that the Alexander Hawkins/Elaine Quartet was working the material from UpRoot (Intakt, 2017), but bar the smattering of lyrical vocal parts with their sotto voce accompaniment, the line between composed and improvised music was blurry at best.

An extended piano, bass, drums segment saw Hawkins conjure peeling bell-like sonorities and Afro-Caribbean rhythms amidst thumping block chords in a passionate display, with Charles [Tomorrow's Warriors, Empirical, Zed-U] and Davis [Bourne/Kane/Davis] forging no less dramatic paths. Mitchener and Davis then embarked upon a duo improvisation, the singer's animalistic soundings and the drummer's fidgety invention evoking the teeming life of a rainforest with a storm brewing. The storm when it broke saw Mitchener soar over the fiercely rumbling rhythms, though even within the storm's eye there were, if you tuned in, tremendous subteleties at play—delicate touches and very precise articulations.

An unaccompanied bass solo morphed into a killer ostinato, kick-starting an infectious movement of bluesy swing—the backdrop to Mitchener's spoken-word poetry-****-singing. It was as if Jeanne Lee and Charles Mingus had conspired to provoke some serious mischief. After an uninterrupted hour of this captivating performance the gaping pocket of silence eventually broke, ushering in generous applause from the clearly enthused audience. For the encore the quartet offered up the short piece "Joy," a strikingly sombre yet lyrical vignette; bowed bass, elegiac piano, whispering brushes and Mitchener's softly operatic one-word incantation combined in something akin to a prayer of hope.

Much of the Haw...

Adventurous pianist Alexander Hawkins seems intent on exploring as many different avenues of expression as is humanly possible, having already released solo set Song Singular, (Babel, 2013), duo set Leaps In Leicester, (Clean Feed, 2016), trio set Alexander Hawkins Trio, (AHM, 2015), and ensemble set Unit[e], (AHM, 2017), as well as documents of rewarding encounters with outfits as diverse as Rob Mazurek's Chicago Underground and Turkey's Konstrukt. Uproot represents a new venture for him as he teams up with vocalist Elaine Mitchener, as well as familiar collaborators bassist Neil Charles and drummer Steve Davis.

But this album is a long way from the traditional piano trio with vocals. Indeed it is not until part way through the third track that the typical formulation appears. Mitchener builds on the Jeanne Lee, Maggie Nicols and Norma Winstone models for incorporating voice into an improvising setting. She switches between variously making wordless noises which express the full range of human emotion and then some, and speaking, singing and scatting. Her fluidity is matched by her colleagues. Both Charles and Davis move easily between the composed and the improvised episodes blurring the boundaries, while Hawkins subtly steers and shapes from behind the keyboard.

Together they form a totally integrated unit which achieves a satisfying balance between vocals and instrumental. They share an empathetic sense of dynamics, apparent from the start, but most obvious in how they navigate as a crew the sudden swells, lacunas and spiky pointillism of "The Miracle / You." While "If You Say So" is the only all-out improv, there are uncharted elements in all the other cuts, which include Hawkins's originals as well as a variety of intriguing covers by 1960s New Thing icons like Patty Waters, Jeanne Lee and Archie Shepp.

Testament to the group ethos, Hawkins doesn't solo until the title number, where he spins out a tripping yarn over left-hand figures evoking South African kwela rhythms, before an unaccompanied, rippling close. "OM-SE / Environment Music" forms the highlight encompassing among other things a duet for Davis's tappy rumble and Mitchener's voice, a rhapsodic piano solo, an intermittent group refrain, throbbing pizzicato calisthenics from Charles, and Mitchener declaiming a prosaic list of items to declutter all in just over 13-minutes. It represents in microcosm the range of this alluring band.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/uproot-alexander-hawkins-intakt-records-review-by-john-sharpe