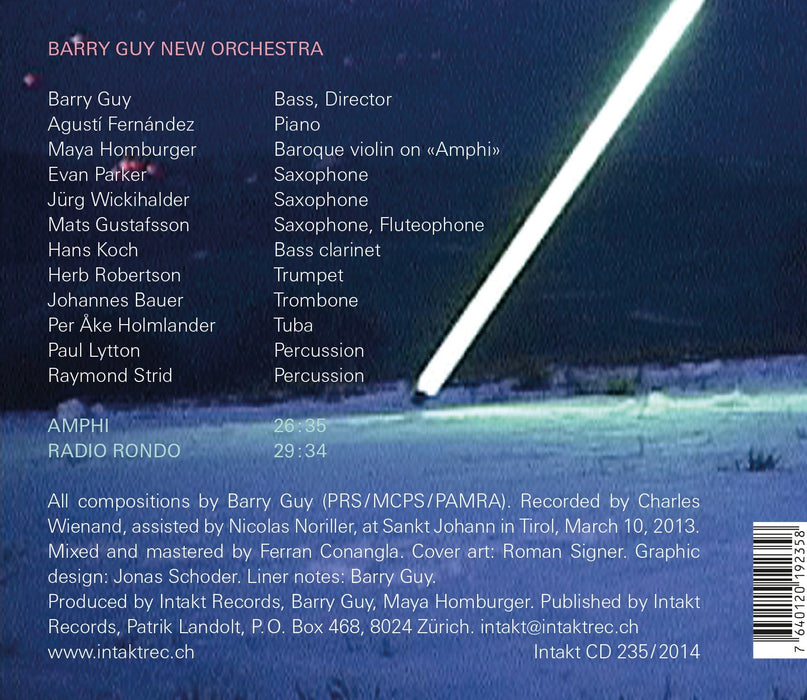

235: BARRY GUY NEW ORCHESTRA. Amphi, Radio Rondo

Intakt Recording #235 / 2014

Barry Guy: Bass, Director

Agustí Fernández: Piano

Maya Homburger: Baroque violin on «Amphi»

Evan Parker: Saxophone

Jürg Wickihalder: Saxophone

Mats Gustafsson: Saxophone, Fluteophone

Hans Koch: Bass clarinet

Herb Robertson: Trumpet

Johannes Bauer: Trombone

Per Åke: Holmlander Tuba

Paul Lytton: Percussion

Raymond Strid: Percussion

Recorded at Sankt Johann in Tirol, March 10, 2013.

More Info

The French magazine „Jazzman“ placed Barry Guy’s first release of the New Orchestra among its records of the year (“a scalpel from the first second”) and the „Neue Zürcher Zeitung“ called his composition “a masterpiece looking toward the future.” Nine years after the successful debut album Inscape-Tableaux, and five years after the second recording Oort-Entropy Barry Guy and his New Orchestra present their third release with two compositions of Barry Guy: Amphi and Radio Rondo. Barry Guy writes: «As always I try to structure the composition to place all the players in a creative dialogue with each other, carefully grading the tensions and releases in the music to take the listener on – Amphi may be termed as “chamber music” whilst Radio Rondo looks towards a more orchestral landscape. In some ways, the listener must also adjust their expectations since the expansiveness of the concert grand piano resonating within an obvious “big picture” as in Radio Rondo, differs markedly from the (no less resonant) more internalized musical gestures of the baroque violin in Amphi. Importantly, the musicians in the BGNO deliver improvisations of nuanced sensibility in response to two quite different compositional strategies.»

Album Credits

Cover art: Roman Signer

Graphic design: Jonas Schoder

Liner notes: Barry Guy

Compositions by Barry Guy. Recorded by Charles Wienand, assisted by Nicolas Noriller, at Sankt Johann in Tirol, March 10, 2013. Mixed and mastered by Ferran Conangla.

The disc showcases the BGNO's rendition of the two titular charts by the British bassist. Renowned as a composer who makes space for improvisation an integral part of his scores, Barry Guy has followed a well-established template by retooling existing works specifically for the BGNO. Though influenced by contemporary classicism as much as jazz, the end result is unique to Guy. He begs the question of what an improvising ensemble in the 21st century can be and provides an answer which satisfies both the head and heart: cerebral yet packing a visceral punch.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/john-sharpes-best-releases-of-2014-by-john-sharpe

Ils sont également douze dans le Barry Guy New Orchestra pour la première des deux longues suites qui composent ce disque, Amphi, pièce en sept parties “écrite“ pour sa compagne, la violoniste baroque Maya Homburger. Comme à son habitude, Barry Guy joue sur les masses orchestrales mouvantes, laissant une large place à l’aléatoire, et qui renforcent les dissonances maîtrisées du violon. Une œuvre très “musique contemporaine“ qui ne me manque pas d’ampleur. L’autre pièce, sans Maya Homburger, Radio Rondo, apparaît plus “violente“, avec un début très free et, plus généralement, un foisonnement orchestral dense et dur, qui met cette fois en valeur le piano “déconstruit“ d’Agusti Fernández. Notons que cet exercice collectif difficile est négocié par des improvisateurs de haut niveau, dont certains, comme Evan Parker ou Paul Lytton, se fréquentent depuis des décennies.

https://www.culturejazz.fr/spip.php?article2553

Twee stukken van elk ongeveer een halfuur vullen deze cd. Ze verschillen duidelijk van elkaar: een schriel gestreken bas opent Amphi en gaat een duo aan met de barokviool van Maya Homburger. Het stuk ontplooit zich majestueus in lange, trage bewegingen met een mooie dramatiek en plaatst ons in een wijd landschap (op deze aardbol of een andere planeet, dat kies je zelf). Radio Rondo is veel gewelddadiger en vertolkt de boze energieke freestijl uit de jaren 60. In de helft van de tijdspanne ontstaat er een geschreven thema, dat het ensemble nog een paar minutjes laat ontplooien in gramschap en verontwaardiging, om dan in staccato-gesprekjes neer te dalen. Hiervoor zijn vooral de koperblazers en piano verantwoordelijk, maar de storm breekt terug los en dan monden we weer uit in een geschreven partij: onheilspellend en met die dramatiek van de eerste track.

Naar het einde toe krijg je een Stravinsky-gevoel, maar in de laatste minuut incasseren we nog een stevige mep op ons gezicht. Enfin, het bekende recept, dat ons wat aan het ICP-orkest doet denken.

To be honest, I disliked “Radio Rondo” after first listening to Amphi/Radio Rondo. I’ve long been a fan of Barry Guy’s New Orchestra, the London Jazz Composer’s Orchestra, and nearly every member of the band in their countless projects and solo ventures. Last year’s Mad Dogs was one of my favorite releases of the year, and I was impressed with “Amphi” as it came to a close. But upon reaching the full band free jazz freak-outs in “Radio Rondo,” I wrote this in my notes:

“large portions of ‘Radio Rondo’ represent a strain of improvisation that’s becoming harder and harder to justify. All of the players involved are far more talented and nuanced than their combined cacophony suggests. Pieces like this offer a retreat from thoughtful improvisation by providing a dense thicket to hide in.”

A little later in the day, I was reading from Ajay Heble’s excellent Landing on the Wrong Note: Jazz, Dissonance and Critical Practice when a question was posed in the text: is musical meaning a function of intent or effect? For my money, the two aren’t mutually exclusive. Meaning will always be a subjective blend of the two: the production of music is clearly an intentional act, and in the listener an effect is wrought, often as a result of experiences, moods and environments that are quite unrelated to the music at hand. In a way, there’s an additional tier of harmony that overlays the production and consumption of music: the consonance or dissonance between intent and effect. Free improvisation is interesting because in many ways it deals in dissonance at this level, too. There can be much discord between the intent of musicians and the effect that’s ultimately produced in most listeners.

Attempting to resolve this tension, the next day I sought out the earlier recording of “Radio Rondo” made with the London Jazz Composer’s Orchestra and Irene Schweizer. I found the burbling intensity to be more convincingly borne by the broader brass palette and use of strings, rather than the shrieking reeds that dominated my hearing of the New Orchestra. The strong effect of the earlier version poised me to reevaluate the new one. I returned again to Amphi/Radio Rondo, and my experience was much different. I could better sense the orchestral sweep of the piece, could discern more of its structure, how everything continually circled back to Agustí Fernández’s incredible piano performance. What was previously overwhelming seemed tempered now, and perhaps just as much as “Amphi,” I could see “Radio Rondo” as a function of Guy’s devotion to inhabiting the world of new classical music while leaving a foot in the unruly history of free jazz, too.

Though there’s nothing overtly political in Guy’s music, it comes from a long line of music in which a certain political stance is implied—the politics of struggle, regardless of whether a European or African-American path is taken to reach improvised music in its present state. Even if we never consciously consider it over a lifetime of listening, part of me wonders whether we’re ever immune to the social politics that underlie this music. For some, free music represented the very real struggle of human rights, but even at its most innocuous the music has always been a protest against the status quo, against rigid perceptions about what constitutes “real” music.

What felt different while I listened was that sheer volume and density no longer seem like the best ways to rebel. The power of a group blaring in the red is undeniable, but it also felt unsustainable. The screaming cacophony is what blazed the trail that leads to the New Orchestra today. Anger and intensity cleared the ground so that so much more could be said; hadn’t the need to shout diminished? I still believe that part of what allows the listener to fashion a bridge over the self-indulgence inherent in a lot of improvisation is the idea of a shared or—at the very least—vicarious catharsis. Rather than a release, my first listen felt more like being attacked. As I’ve listened again, I’m beginning to see how my bridge might be crafted—how I might align their intent with what I’m hoping to experience. It’s easy to misinterpret, and I want to be fair. There’s space for a limitless range of emotions in the New Orchestra’s clamor. It seems to me more and more that violence or anger or rebellion are the things that I brought to the table as I listened that day.

Part of what prompted such a struggle over “Radio Rondo” was the truly great effect of the preceding piece, “Amphi.” Joined by Maya Homburger’s Baroque violin, the New Orchestra is used to add color and tension to a piece Guy originally wrote as a duo for violin and bass. It brings to mind the way Luciano Berio transformed his solo Sequenzas into the orchestral Chemins. This isn’t the only classical touchstone in “Amphi”—the piece drips with the influence of many 20th century greats. Ligeti and Xenakis lurk in the atonal rumblings of the ensemble, and the Spectralists—Murail, Rad...

Another musician whose compositions are influenced by visual art as well as architecture and other sounds is British bassist Barry Guy. Amphi, Radio Rondo (Intakt CD 235), demonstrates how he uses his 12-piece New Orchestra (BGNO) to frame solo concertos. Suggested by Elana Gutmann paintings, “Amphi” places Maya Homburger’s structured soloing on baroque violin within the context of polyphonic eruptions from the BGNO. While the initial sequences suggest that violin interludes are trading off with band parts, by the final movements the string part is firmly embedded. Even before that, Homburger’s expressive spicatto sweeps and staccato scratches are prominent enough that clusters of reed buzzing, brass lowing or clumping percussion appropriately comment on her solos. Helped by a pulsed continuum from pianist Agustí Fernández, tubaist Per Åke Holmlander and Guy’s double bass, her tremolo string vibrations harmonize alongside the horn-and-reed section before the climax, where every instrument’s timbres deconstruct into multiphonic shards. Moving upwards from near silence to a crescendo of yelps, cries and trills, the fiddler’s centrality is re-established with a coda of strident scrubs. Fernández is also the soloist on the slightly lengthier Radio Rondo. Here though his passing chords and cascading runs face head-on challenges from others’ extended technique, including Evan Parker’s circular breathed soprano saxophone smears and speedy slurs from trombonist Johannes Bauer. The keyboardist’s high-energy key fanning and kinetic cascades inject more energy into the proceedings plus emotional dynamics. Confident, Fernández mixes the physicality of a concert pianist with the close-listening of a big band soloist like Earl Hines, as a series of ever-more dramatic crescendos solidify the ensemble into as much pure swing an experimental ensemble can muster, complete with blasting high notes from trumpeter Herb Robertson. With the architectural structure of the piece finally apparent, the final rondo could be the soundtrack for an experimental war film, with agitated piano comping, plunger slurps from the brass and reed multiphonics as well as pounding percussion. Just when it seems the peak can’t be heightened, the piece abruptly ends as if a radio has been switched off. It`s an exhausting yet exhilarating triumph.

Across these two compositions for his current 12 piece ensemble, Barry Guy explores the dynamics of placing a solo voice in dialogue with constantly shifting instrumental configurations. "Amphi" is built around the simultaneously rich yet brittle sound of Maya Homburger's Baroque violin as she negotiates a series of brief, tightly scored flashes, strung out like concentrated beads on a necklace of much looser group improvisation. Snuffling trombone and tuba, rippling piano and tight, insistent ✓saxophone take turns to gently interrogate the violin, courting its delicacy with restrained subtlety. "Radio Rondo" is a much more boisterous piece, with massed horn squalls and thumping percussion dropping down into garrulous smaller groupings, and Agusti Fernández's nervously chattering piano commentary seeping into the gaps in the rise and fall. What's impressive is how these intrinsically episodic structures are - approached with a patient and attentive sense of narrative development, giving both a gripping and coherent linear logic.

Barry Guy is powerful presence on the UK scene, with a discography that dates back to the Spontaneous Music Ensemble in the 1960s and features superb subsequent work with Tony Oxley, Howard Riley, Evan Parker and Peter Kowald among numerous others. His versatility, both as a composer and as a musician, is reflected in the breadth of these two tracks: one that might be broadly characterised as chamber music, the other more orchestral, but both also drawing heavily on the vocabulary of leftfield i jazz. Radio Rondo could have been recorded by an orchestra infiltrated by improv musicians, while improv's stabs and stutters, flurries and flutters also feature now alongside baroque violin - on Amphi. It's a beguiling, frequently startling mix of chaos and order, and there is first-rate musicianship from the likes of longstanding collaborator Evan Parker - as well as baroque violinist (and Guy's wife) Maya Homburger, featured to superb effect on Amphi.

La Barry Guy New Orchestra es algo parecido a un enorme instrumento. En manos de su líder, el contrabajista y compositor Barry Guy, esta formación que reúne a algunas de las figuras en primera línea de la improvisación europea (Evan Parker, Agustí Fernández, Mats Gustafsson, Paul Lytton, Raymond Strid…) muestra una versatilidad abrumadora. En su nueva grabación en Intakt, Amphi. Radio Rondo, este super-grupo interpreta las dos composiciones que le dan título.

En la primera de ellas aparece como invitada Maya Homburger, violinista especializada en el barroco y compañera de Barry Guy. Ambos tienen una carrera discográfica muy amplia con proyectos de música barroca y contemporánea en sellos como ECM y Maya Recordings. Otra cuestión es su trabajo -grabado- en los terrenos de la libre improvisación, o en una formación como la Barry Guy New Orchestra. Si bien esta artista ya había aparecido en el monumental Mad Dogs, que recogía grabaciones realizadas por distintas agrupaciones surgidas de la Barry Guy New Orchestra, lo hizo en un único tema: “Celebration” es una composición de Barry Guy que la violinista interpretaba a dúo en compañía del baterista Paul Lytton.

En “Amphi” por fin hay la oportunidad de escuchar a esta exquisita violinista integrada en esa enorme máquina de crear sonidos. Este tema está construido en torno suyo. La intensidad habitual (presente en “Radio Rondo” desde el mismo inicio) y el sonido del conjunto desaparecen. En su lugar, aparecen pequeñas agrupaciones de músicos, en las que Maya Homburger tiene un papel preponderante, y a quien se escucha realizar algún solo en el que resulta una delicia escuchar su violín barroco. El resto del grupo se adapta perfectamente a esta situación. Los tutti del grupo o los solos intensos que tienden al expresionismo (que trufan “Radio Rondo”) no son el único terreno en el que estos músicos se mueven a placer.

El contraste entre las dos composiciones es justamente uno de los elementos que hacen de Amphi. Radio Rondo una obra especialmente atractiva, ya que añade nuevos matices al trabajo de Barry Guy con su New Orchestra.

Some more, Mr. Nice Guy!

Barry Guy, auch so eine Lichtgestalt der Gründergeneration der Bewegung frei improvisierender MusikerInnen in England, bekleidet die Funktion eines herausragenden Konzeptualisten, Anregers, Leiters improvisierender Großensembles. Und das schon seit über vier Dekaden. Guy, ebenso exzellenter Bassist, hat einen wegweisenden organischen Ansatz zur Zusammenführung von notierter Musik und freier Improvisation ausgetüftelt. Beide musikalischen Schöpfungsakte finden in seinen Stücken eine anregende, engvernetzte Balance.

....

Hier ist Guy wieder in seinem Metier. Für das von ihm geleitete, aus dem LJCO hervorgegangene New Orchestra (Agustí Fernández, Maya Homburger, Evan Parker, Jürg Wickihalder, Mats Gustafsson, Hans Koch, Herb Robertson, Johannes Bauer, Per Åke Holmlander, Paul Lytton, Raymond Strid) hat er wieder zwei fulminate Klang-Epen, die seine PartnerInnen kongenial miteinbeziehen, entworfen. Kokettiert die Komposition Amphi – quasi ein „Konzert für Barock-Violine und Orchester“, Solistin ist Maya Homburger – betreffend ihrer Klangqualitäten und -eindrücke auf sehr flexible, freimütige Weise mit Aleatorik/ Serialismus, so bricht Radio Rondo, wie der Titel schon verrät, an die klassische Rondoform mit prägnantem Anfangsteil angelehnt, mit ziemlicher Vehemenz hervor, ohne jäh der Unkontrollierbarkeit anheimzufallen. Dazu ist die Formidee zu ausgereift und den Musikern, allesamt bekannte jahrelange Weggefährten von Guy, deren Ausformulierung ein zu wichtiges Anliegen. Die beiden Stücke – aufgenommen während der artacts'13 in der Alten Gerberei von St. Johann/Tirol – zeigen erneut die gegenseitigen, einander bedingenden Polaritäten von Guys großorchestralen Visionen. Feinstoffliche Flächigkeit in divergierenden Intensitätsstufen einerseits und überwältigende Clusterhäufungen bzw. Jazz-immanente, heißspornige Energetik andererseits. Tragende Elemente sind die individuellen Stimmen der MusikerInnen, gepaart mit ihrer ausnehmenden Musikalität. Zwei weitere Kompositionen im beeindruckenden Werkkanon des Meisters der „improvisierten Sinfonien“.