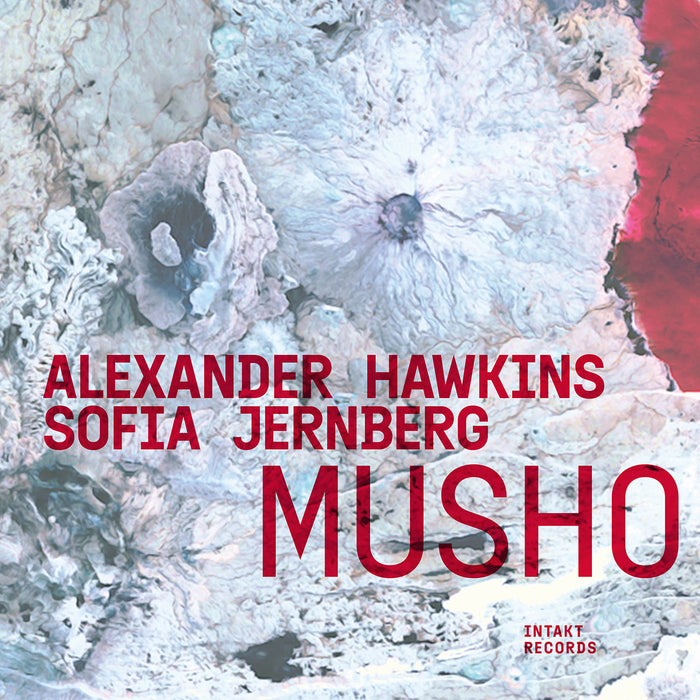

420: ALEXANDER HAWKINS – SOFIA JERNBERG. Musho

Intakt Recording #420 / 2024

Sofia Jernberg: Voice

Alexander Hawkins: Piano

More Info

Sofia Jernberg und Alexander Hawkins gehören zu den facettenreichen und ausdrucksstarken Musiker*innenpersönlichkeiten mit einem überraschenden Aktionsradius. Die schwedische Sängerin Sofia Jernberg lotet die Grenzen der Gesangstechnik in einer Vielzahl von kreativen Kontexten aus, die von Schönbergs Pierrot Lunaire bis zu Mats Gustafssons Fire! Orchester reichen. Alexander Hawkins wird oft als unvergleichlich in der modernen kreativen Musik beschrieben und gilt als einer der innovativsten und einfallsreichsten Pianisten und Komponisten der zeitgenössischen Musik. Im Duo werden traditionelle Lieder aus Äthiopien, Armenien, Schweden und anderen Ländern Ausgangspunkt für die Entfaltung einer spannenden und sehr persönlichen Klangwelt. David Toop schreibt in den Liner Notes: «Where is home, where is return for the scattered? Soft and crystalline, a music of edges, silence and tangential shoots, Musho dwells in these questions, invites the listener to consider displacement, migration, identity, responsibility, bloody history, the seepage of culture and community, but more than that, invites listening.» Musho ist ein fantastisches Werk musikalischer Gegenwärtigkeit.

Album Credits

Cover Art: Yonas Kidane

(Detail from an image available under CC BY-SA 2.0 Deed)

Graphic design: Paul Bieri

Liner notes: David Toop

Photo: Niclas Weber

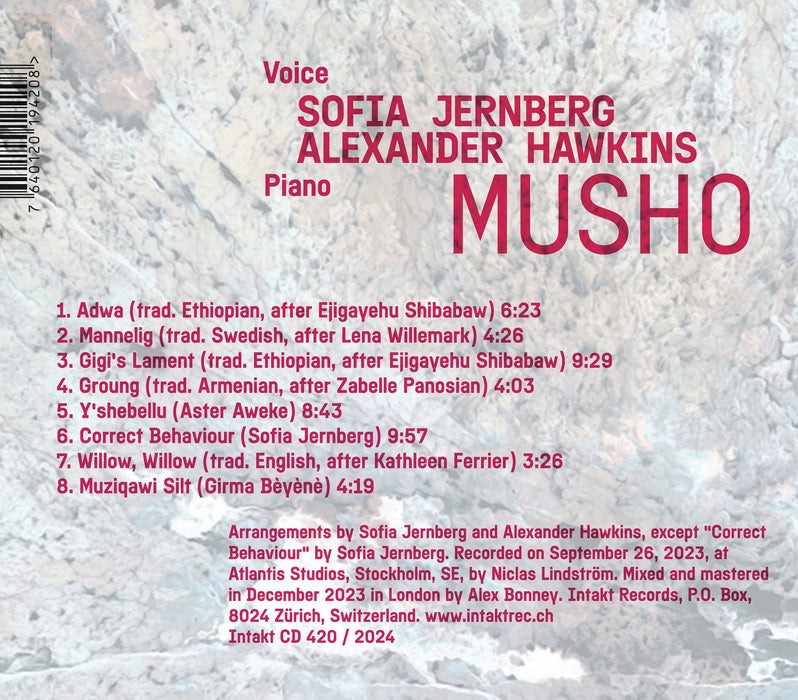

Arrangements by Sofia Jernberg and Alexander Hawkins, except "Correct Behaviour" by Sofia Jernberg. Recorded on September 26, 2023, at Atlantis Studios, Stockholm, SE, by Niclas Lindström. Mixed and mastered in December 2023 in London by Alex Bonney. Produced by Sofia Jernberg - Alexander Hawkins and Intakt Records. Published by Intakt Records.

Her artistry 'stems from having grown up in two counties that defeated the West: Ethiopia and Vietnam'

CHRIS SEARLE speaks to Ethiopian vocalist SOFIA JERNBERG

PERHAPS it was her childhood experiences that have made the Ethiopian singer Sofia Jernberg such a powerful and audacious musical internationalist. Her new album, Musho, allied with the brilliant and empathetic Oxford-born pianist Alexander Hawkins, has songs from Ethiopia, Armenia, medieval Sweden and Shakespearian England. And she states with pride that her artistry “stems from having grown up in two counties that defeated the West: Ethiopia and Vietnam.”

“I was born in Addis Ababa in 1983 and grew up with a single mother who adopted me while she was working as a diplomat in the Swedish embassy. She worked in Ethiopia and Vietnam before we arrived in Sweden when I was 10, when she started work at the Swedish International Development Agency. We had an electric piano and record player at home and I listened to music from all over the world. The LP player became my best friend. I was constantly singing, but never thought it could be a profession until I was in my mid-teens.”

“I speak four European languages well, but understand many more. My mother spoke Amharic and loved Ethiopia, so it has always been a part of my life, but its culture for me was always connected to a deep sorrow and involuntary separation. Ethiopia went through a lot in the ’80s and ’90s, and we engaged closely with that.

“I didn't know what jazz was until my teenage years. Before that my interest was Western classical music. But I was always curious about all kinds of music, and as I looked at jazz shelves in libraries and record stores that curiosity deepened. I struggled to understand it, did all the listening to myself and never talked to anyone about it. I went to jazz concerts and avant-garde performances by myself, never talking to anyone about it. I never studied music at a higher level, but learned what I needed — how to read and write music and learned by doing, listening to and playing records of musicians I admired.

“I didn't become a full professional singer until I was 30, but had stood on a stage and sung regularly since I was 10, since I went to choir school.”

She developed a love of many art forms, including dance and visual performance. “I chose music because it’s a language in itself. It brings people together and unites us in a strange way. I sing with people who often have opposite views to myself, who are twice my age and who I would never meet otherwise. All the ugly social structures go away when we make music. I’m a musician rather than a singer, and I sing without words for a whole concert to achieve that. Words can sometimes get in the way, and singing without them means that everyone, regardless of language, can access what I sing.”

What about her partnership with the protean Hawkins?

“We met when the musical director of Bimhuis, the Netherlands jazz club, put us together. I love Alex’s ambition, dedication and creativity in his life of music and piano, constantly pushing himself, always evolving and surprising me with the most magical moments. His musical knowledge is very rich and we share a love for all kinds of music, which is why I so often learn something new or different, because of something he said.”

Why is the album called Musho?

“It means ‘sad song’ in Amharic, and it was clear from the start that we would play melancholic music. My favourite track on the album is Willow, Willow, Desdemona’s lament from Othello. I was so pleased that Alex wanted to play something English, for the English music tradition connects us and has given me so much.”

Musho exemplifies the gloriously syncretic power of jazz, and Hawkins’s always surprising pianism unites with Jernberg’s voice in a brotherly musical fellowship to her surging, saddening and always deeply moving voice. When she sings the traditional Ethiopian song, Adwa, remembering the victory of Ethiopian forces over the invading Italian army in 1896, there is both a defiance and soulfulnness in her voice that eclipses all genres.

In that sense her voice embodies the cosmopolitan spirit of Robeson, Makeba, Peggy Seeger, Woody Guthrie and Nina Simone, and has a global reach which sings for all humanity.

Musho is released by Intakt records

https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/her-artistry-stems-having-grown-two-counties-defeated-west-ethiopia-and-vietnam

I was fortunate to witness the first time singer Sofia Jernberg and pianist Alexander Hawkins performed together in Amsterdam at the October Meeting organized by former Bimhuis director Huub van Riel back in 2016. Jernberg is of Ethiopian descent and had worked with Hailu Mergia, while Hawkins continues to work regularly with Mulatu Astatke, so the two tunes they performed at their auspicious debut were from that nation’s rich repertoire. In the years since, however, the duo has expanded its material to include folk themes from as far afield as England, Armenia, and Scandinavia—to say nothing of an original tune by Jernberg that turns up on this stunning album. The interpretations maintain clear connections to the source material, but as improvisers of unbounded originality and wide-eared aesthetics Jernberg and Hawkins liberate the songs from any single location or tradition. The pair are vividly attuned to one another, generously ceding space, offering complementary accents, and locking in on elusive lyrical shapes with the lightest touch, translating global traditions into a singular chamber sound, whether the soaring beauty of “Gigi’s Lament,” a traditional Ethiopian song Jernberg learned from the overlooked Ejigayehu Shibabaw, or the devastating, otherworldly “Groung,” an Armenian ballad learned through the version waxed by Zabelle Pasosian. Within the melodic invocations are loads of expressive extended techniques which always feel part of the broader fabric of the performances.

https://petermargasak.substack.com/p/my-40-favorite-albums-of-2024-part

When faced with Musho’s cover, one must be struck by the fact that the singer’s name comes below the pianist’s, for the convention tells us that it should be the other way around, even in cases where the latter happens to be the main composer. This subtle subversion is itself telling: Musho shouldn’t be taken as different in kind from Hawkins’s other duo collaborations with notable women musician-composers such as Tomeka Reid, Angelika Niescier or Nicole Mitchell. There’s a more substantial view implicit here: even when performing songs (with words), the voice is simply another instrument (with its own unique features, of course), on a par with the cello, the saxophone, or the flute; and the singer is simply another musician, here on a par with the pianist. The conventional singer/accompanist hierarchy is thus shattered, and so both singer and pianist are emancipated: they are still free to stick to more or less conventional roles, if they so wish, but can also embrace all the remaining possibilities their instruments offer; and, crucially, they present themselves to audiences as equals: a genuine duo of musician-composers.

The singer qua musicianconception (and its voice qua instrument counterpart) has been prominent in creative music for some time now, but few have made as powerful and persuasive a case for it as Jernberg. She is the ultimate anti-singer, in a sense that goes even beyond the emancipation of her instrument: while breaking new ground at the musical (or sonic) level, she rejects all sorts of extra-musical diversions that often intrude the ways in which artists (especially women singers) are publicly perceived (and judged), namely uses of her image for marketing purposes or stage performance antics. This is not just as an artistic statement but a political one, radically at odds with the kind of liberal (pseudo-)feminism that preaches “women’s empowerment” without seriously questioning the very power dynamics that foster the oppression of women in the first place. And she does all this while being one of the most formidable singers around, with a gorgeous (and instantly recognizable) timbre and mind-blowing technical resources, which she deploys with a rare intelligence and taste.

Together with Hawkins, another true musical polymath, Jernberg has created a sound world that is both genreless and timeless, and as interesting as it is moving: a song cycle comprising material from various traditions (Ethiopian, Swedish, Armenian, English), but arranged and performed in such a way so as to form a single cohesive aesthetic, both breathtakingly beautiful and new. And, despite such cohesiveness, one is still able to trace what is peculiar to each of these traditions, i.e., we get a form of universality that does not overwhelm locality. (Here, too, one is bound to think of salient political analogies.)

Musho is a definite highlight of Hawkins’ already rich discography. And it is the perfect entry point into Jernberg’s art.

https://www.freejazzblog.org/2024/12/sofia-jernberg-and-nick-dunston-anti.html

Der kraftvolle Pianist aus Oxford, die Stimmkünstlerin aus Äthiopien: Vertreibung, Migration, Identität, Blut. Und hören, hören

Alexander Hawkins: La Musica è uno Spazio generoso

Nato a Oxford nel 1981, Alexander Hawkins è musicista di punta della propria generazione e della scena contemporanea internazionale. Persona di grande disponibilità e affabilità, è tra i pochissimi musicisti che nella sua fascia di età si confrontano in modo congruo al temperamento dei pionieri che dagli anni Sessanta in poi si sono avvicendati sulla scena della musica afroamericana. È costantemente chiamato a collaborare da questi personaggi per la sua duttilità stilistica, per la preparazione, per l'attitudine a esplorare, per la vasta competenza nei confronti di approcci e linguaggi differenti.

La sua figura artistica e la sua attività multiforme, ricca di contatti in ambiti diversi, è stata descritta in modo meticoloso e dettagliato da John Sharpe per All About Jazz in un'ampia intervista del 2013, alla quale rimandiamo senz'altro. Abbiamo incontrato Hawkins di recente al Berliner Jazzfest, dove era presente in due occasioni: contesti molto diversi, che rispecchiano parzialmente, ma efficacemente la sua attività così articolata ed esplorativa, così originale.

A Berlino si è esibito con il rodato trio Decoy alla Haus der berliner Festspiele, nella versione allargata alla presenza del polistrumentista Joe McPhee, che con i suoi ottantacinque anni, compiuti proprio in quei giorni, è una vera icona della musica nera e dell'improvvisazione contemporanea, un punto di riferimento profondo. Nello storico festival tedesco, che quest'anno compiva i suoi sessant'anni, Hawkins si è anche esibito in duo con la vocalist svedese Sofia Jernberg, in un concerto al club A—Train. La nostra chiacchierata ha preso il primo spunto proprio da questa significativa collaborazione.

All About Jazz: Nelle intenzioni di voi protagonisti e nelle note al vostro CD di David Toop, la proposta del duo con Sofia Jernberg invita a prendere in considerazione criteri forti, come spostamento, migrazione, identità, responsabilità, ascolto intuitivo... Nella tua percezione, il rapporto con queste componenti, in particolare l'ascolto, è cambiato dai tuoi inizi al momento attuale?

Alexander Hawkins: Penso che sia una domanda molto interessante, perché non siamo soliti pensare all'ascolto in modo prospettico. È come osservare qualcosa: se ti trovi a un'estremità di un ponte, la visione è diversa rispetto all'altra estremità. E penso che lo stesso valga per l'ascolto. Il contesto e l'esperienza cambiano il modo in cui percepiamo i suoni... li percepiamo e li organizziamo. Quindi, suppongo, inevitabilmente, di sentire le cose in modo diverso rispetto, diciamo, a vent'anni fa. La domanda più difficile è... "Come è cambiato l'ascolto?." In che modo è cambiato? Ad esempio, il mondo così com'è al momento mi rende consapevole che la musica è qualcosa di fondamentale e potenzialmente universale, ma anche qualcosa di molto fragile, di precario.

Sai, è un grande privilegio poter fare ciò che facciamo, in un momento in cui ci sono persone a pochissimi chilometri da qui che non hanno accesso all'acqua potabile o che vengono uccise quotidianamente. Siamo consapevoli che il suono è universale, ma anche che è un privilegio. Dovrebbe essere un diritto, ma oggi è un privilegio. In questo senso, ciò modella la nostra prospettiva d'ascolto. Un concerto permette di trasmettere delle esperienze condivise: una cosa molto interessante, che rende la musica davvero preziosa. Ma a volte ci si può sentire anche banali, se non c'è la consapevolezza di quanto si è fortunati. C'è una cosa rilevante, che penso abbiamo visto nel corso della storia della musica: questa può essere un potente strumento sociale. A certi livelli, però, siamo vulnerabili e impotenti.

AAJ: La tua è una riflessione profonda.

AH: Questa tematica mi sta a cuore, è molto interessante. So che ai musicisti piace presentare sé stessi come radicali e socialmente impegnati, e credo che questo sia importante, ma le persone davvero radicali sono quelle impegnate sul campo, sono le persone che lavorano nella sanità, che lavorano con i rifugiati. Ecco le cose che vanno a interagire con i nostri contesti di ascolto. Ci fanno pensare in un modo molto serio al mondo e al suono, alla canzone e all'esperienza. Purtroppo, trattandosi di un orizzonte così ampio, non so bene come affrontarle. Ecco, penso che la cosa importante di questioni così, sia che ci coinvolgono tanto come ascoltatori quanto come performer. Ci dovrebbero portare a riflettere sulla nostra situazione e forse alla fine questo fa parte delle potenzialità di questo approccio, che ci aiuta, si spera, a ragionare verso la realizzazione di un cambiamento sociale dalle ampie dimensioni.

AAJ: Grazie, Alexander, per questa risposta così articolata e sensibile. Fissiamo ora l'attenzione sul duo: ci sono tanti ingredienti: dalla musica popolare alla canzone, all'improvvisazione. Nel confronto con i numerosi altri incontri in duo che hai realizzato, qual è la caratteristica specifica di questo?

AH: A...

At festivals in Italy and Portugal in March and May of this year, I met and talked about music with Oxford pianist, organist, composer, bandleader and teacher Alexander Hawkins, who was premiering his new quintet and playing with Michael Formanek, Ricardo Toscano and Tim Berne. An avid record listener and fan, with tastes ranging from classical to global, soul, jazz and beyond, this passion led him to hosting the weekly radio program “Break a Vase” starting in 2023 (on mixcloud then reprised on the online radio station OneJazz), where he talks about favorite tracks selected for audiences to get acquainted with or revisit. Before he embarked on a series of dazzlingly diverse gigs in the US, from San Francisco to Ann Arbor, and then more shows in Europe, he agreed to browse through his shelves and extract seven discs that mean a lot to him, for any reason, be it influential pianism, production qualities, pure listening pleasure or composed works he finds baffling.

Alexander Hawkins:

I love this type of interview where I get to choose records to talk about them because, ultimately, I’m a music fan as much as I am a musician. I think the two are part of the same thing. It’s also horribly difficult to talk about albums. Being asked to talk about albums is a little like free improvisation: it’s not as free as you might think; this is a different interview – but that’s one of the reasons why I personally steer clear of completely free improvisation in my own practice. The point is that the choices are so varied that there’s a bit of a brain freeze involved. And just like a compositional prompt helps me to be freer in a musical context, I almost like to impose parameters on myself when choosing records. So, for example in this selection I’m going to leave apart some albums which are simply part of my DNA, that I’ve known since I was so little that I just have a non-critical love relationship to them. If I were a robot, these would be pre-installed software. I’m thinking here of things like the Art Tatum trio album with Red Callender and Jo Jones, or the Tatum/Ben Webster record, or the Rex Stewart/Duke Ellington small group session from July 3, 1941 where they play Menelik (The Lion of Judah) and Poor Bubber... Albums like this I’ve known for so long that I just can’t think critically about them, although I love to talk about them. And then, I would love to talk about, you know, what about “five albums I don’t understand” , because that’s an interesting conversation too, or “don’t like but feel I somehow should” , or “ five favorite pianists” or “five albums by living musicians” . In the end what I’ve done this time around is just going to my shelves and pulled some things off because I understand that at some point I’m passionate about whatever I’m listening to, maybe even in a positive or negative way because I feel one of the things I’m getting better at is learning from music that I’m not into, you know, why is that? what do I learn about my musical identity from that fact? and so on. This first album I chose is the Smithsonian Folkways recording of the “Mbuti People of the Ituri Rainforest”. It’s this absolutely stunning polyphonic choral music which I suppose many people will be familiar with. It’s one of the recordings that was actually sent into space as an experience and example of culture to friendly aliens. And I love this music on a very surface level because it’s incredibly beautiful; it inspires me because it has a mysterious quality. I understand what is happening on a technical level, that it’s a music of yodeling and rapid transpositions, a music of hocketing, interlocking parts, and yet even knowing this, it has this mystery and elusiveness quality to it. I feel about these recordings much the same way I do about music of, for example, Bach: astonishing organization and almost because of this degree of order, a great degree of mystery to what’s going on, beautiful and endlessly inspiring, because I don’t quite get it to some level. There’s also by the way an incredible book written by Colin Turnbull, called “The Forest People”, and it was he who collected these recordings in Congo.Second album comes from the classical section of the shelves. On a million occasions I have expressed my deep passion for Maurizio Pollini, a genius pianist who we sadly lost earlier in the year. What I love is that he has this absolute clarity of vision, refusal to compromise, lack of histrionics and a perfect simplicity to his playing. Well, the same is true of the pianist in this selection, which is Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli , one of my heroes on the instrument. One of the recordings I love is that on Deutsche Grammophon, of him playing the Chopin “Mazurkas” . I initially didn’t love Chopin because I have a block against romantic music, I loved the structuralists, Bach and XXth century musicians, and then I frankly got over myself because I realized there was a lot of weirdness and counterpoint and structure...

This playlist is a case study in low-simmering and yet scorching music, handle with care!

Happy listening!

Playlist

Ben Allison "Mondo Jazz Theme (feat. Ted Nash & Pyeng Threadgill)" 0:00

Chris Jennings 5 Ways Home "Ornette's Friends & Neighbours Too " Boy She's The Dandy (Eden River) 0:16

Host talks 5:03

Lampen "Halogen" Halogen (We Jazz) 6:24

Host talks 14:05

Slow Poke "Listen Here" At Home [Reissue] (P&M) 16:00

Alessio Zoratto "For Guernica" Canvas Melodies (doKumenta) 23:35

Host talks 27:39

Alexander Hawkins, Sofia Jernberg "Adwa" Musho (Intakt) 29:45

Micah Thomas "Life" Mountains (Artwork) 35:55

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/sofia-jernberg-slow-poke-chris-jennings-kalle-kalima-and-more

Saxophonist Ohad Talmor has assembled a pool of collaborators, rather than a conventional ensemble, for this unique and fascinating record. The players include: Talmor (tenor, Prophet 10 and MiniMoog synthesizers); Shane Endsley, Russ Johnson and Adam O'Farrill (trumpets); Denis Lee (bass clarinet); Leo Genovese and David Virelles (piano and/or synthesizers); Joel Ross (vibraphone); Chris Tordini (bass); Eric McPherson (drums); plus Grégoire Maret (harmonica). There is no track that features every player, and Lee and Maret only appear once each. Fourteen of the 24 tracks spread across this 81-minute double-album are by Ornette Coleman. Some are well-known (“Kathlyn Grey", "Peace Warriors", "New York”), while others are pulled from an unreleased and therefore unofficial 1998 rehearsal tape that somehow fell into Talmor's hands. (It's safe to assume that copyright issues surrounding that material were what kept this album from being released last year, as originally planned.) Two other numbers, “Dewey's Tune" and "Mushi Mushi”, are by former Ornette bandmate, Dewey Redman, and the remainder, which includes pieces dedicated to drummers McPherson and Gerald Cleaver, are Talmor originals.

Ornette Coleman had one of the most recognizable compositional voices in the history of music -not just jazz, not just Western music, but music, period. He invented a language, spoke it fluently and taught it to others until the end of his life. A few past projects, including John Zorn's Spy vs. Spy and Masada Quartet, Old and New Dreams (the all-star crew of former Ornette bandmates) and Broken Shadows (the quartet of Tim Berne, Chris Speed, Reid Anderson and Dave King), have either interpreted Coleman's material or adapted his language to their own purposes. Back to the Land falls somewhere in between; the melodies are obviously Ornette-ish, but the execution, especially on the chordal instruments Coleman often avoided, is up to the players, and they often take the music to unexpected places. The music on this album is so unified, in fact, despite the changes in personnel from track to track, one could suggest uncharitably that the Talmor originals feel out of place, like interludes breaking up an otherwise conceptually unified release.

4.5 STARS

Alexander Hawkins/

Sofia Jernberg

Musho

INTAKT

HHHH 1/2

Neither Alexander Hawkins nor Sofia Jernberg is

the kind of artist that one can pin down. The

English keyboardist’s CV includes the free-improvising

organ combo Decoy, composing for

the London Symphony Orchestra, exploring the

AACM legacy with Tomeka Reid and accompanying

Ethio-jazz man Mulatu Astatke. The

Ethiopian-born, Swedish-raised singer has played

chamber jazz with Fred Longberg-Holm, sung

Schönberg with the ensemble Norbotten NEO,

dueted with pianist Hailu Mergia and kicked out

the jams with Mats Gustafsson’s Fire! Orchestra.

Their shared experiences with Ethiopian

eminences serve as a starting point, and they’ve

named their project after a style of dirge that is

performed at Ethiopian funerals. But Jernberg

and Hawkins also perform English, Armenian

and Swedish folk songs; the enactment and

transcendence of grief, not the reproduction of

a particular national repertoire, is the point of

this profoundly moving album.

To that end, each has placed restrictions

upon their contributions. Jernberg keeps the

extravagant potential of her extended technique

on a tight leash, and while Hawkins does

not similarly limit himself technically, he sticks

to grand piano. His work under the lid turns the

instrument into a harp and percussion ensemble

on “Mannelig,” sympathetically framing

the singer’s gentle expression of a courtship

lyric fraught with interfaith and interspecies

fault lines. They strip the words from the exile’s

lament “Groung,” distilling it to an inconsolable

melody. But not all is tragedy; when two

musicians finally let loose on “Muziqawi Silt,”

they refashion the Afrobeat anthem into a

deeply personal expression of freedom.

Sofia Jernberg i Alexander Hawkins to zapewne jedne z najbardziej wielowymiarowych i ekspresyjnych osobowości muzycznych dzisiejszej sceny improwizowanej. Ona ze Szwecji, artystka z ogromnym powodzeniem badająca granice technik wokalnych w bardzo różnych kontekstach twórczych, od Pierrot Lunaire Schönberga, przez współprace z Trondheim Orchestra po Gustafssonowką Fire! Orchestra czy freeimprowizatorskie akty w towarzystwie Eve Risser czy Petera Evansa. On, brytyjski pianista, improwizator, nauczyciel często opisywany jako bezkonkurencyjny we współczesnej muzyce kreatywnej, innowator działający z równym powodzeniem jako lider własnych projektów czy towarzysz Anthony’ego Braxtona w jego standardowych eskapadach albo ceniony nauczyciel akademicki.

Razem grają od 2016 roku, ale płytowy dokument ich działalności ukazuje się dopiero teraz, szczęściem nakładem labela tak wielkiej renomy, że jest szansa na to by nie zniknął w odmętach historii fonografii jako ledwie ciekawostka.

Decydując się na działanie w duecie Sofia i Alexander sięgnęli po tradycyjne pieśni z Etiopii, Armenii, Szwecji i innych krajów (jedynie Correct Behavior to oryginalna kompozycja Sofii Jernberg), które jako zestaw poruszają wielki temat diaspory, ludzkich losów, korzeni tych wszystkich których los wygnał z domów, czyniąc z nich jednak nie tyle trywialny statement, co punkt wyjścia do kreacji bardzo osobistego muzycznego kosmosu w formule niebanalnych pieśni z miejscem zarówno dla sugestywnej w swej ludowej prostocie ekspozycji melodii, jak i bardzo nieprostej i jeszcze bardziej nieoczywistej warstwy akompaniatorskiej. Album zatytułowany jest „Musho” i jako składająca się z ośmiu pieśni całość mam wrażenie, że pretenduje do roli o wielę więcej niż kolejnej dźwiękowej ciekawostki z etnicznym kolorytem.

Jest w tej muzyce magnetyzujący powab dzieła unoszącego się wysoko ponad powierzchowną, „fajniacką” folkową zwyczajność. Z drugiej strony jej brzmienie w ożywczy sposób uwolnienia słuchacza od konieczności wylegitymowania się gruntowną znajomością osiągnięć estetyki free improv. „Musho” tym samym stwarza wyborną okazję słuchaczowi oczekującemu niebanalnej, a zarazem nie wprawiającej w intelektualną bezradność muzyki wkroczyć do tajemniczego ogrodu dźwięków, w którym odnajdzie on zaspokojenie, pyszną satysfakcję i poczucie, że rzecz dotyka naszej współczesności głęboko i z ogromną siłą.

https://www.jazzarium.pl/przeczytaj/recenzje/musho