Anmerkungen aus der Presse

NEUESTE NACHRICHTEN

-

Intakt 444: Angel Falls - auf der Bestenliste des Preis der deutschen Schallplattenkritik

Jetzt lesenWir freuen uns sehr, dass SYLVIE COURVOISIER – WADADA LEO SMITH: Angel Falls vom Preis der Deutschen Schallplattenkritik in die diesjährige Bestenliste aufgenommen wurde. Mit einem Platz auf der Bestenliste werden vierteljährlich die besten und interessantesten Neuveröffentlichungen der vorangegangenen drei...

-

Saadet Türköz erhält den Kulturpreis des Kantons Zürich 2026

Jetzt lesenSaadet Türköz hat drei Alben bei Intakt Records veröffentlicht.Jedes Jahr zeichnet der Kanton Zürich eine herausragende Persönlichkeit mit dem Kulturpreis aus.Mit dem Kulturpreis zeichnet der Regierungsrat Persönlichkeiten aus, die ein Lebenswerk von ausgewiesener künstlerischer oder kulturvermittelnder Qualität geschaffen haben, das...

-

Album Release: 448: ALEXIS MARCELO – Solo Piano

Jetzt lesenHappy Release Day! Solo Piano von ALEXIS MARCELOWir freuen uns, unsere erste Kollaboration mit dem New Yorker Pianisten Alexis Marcelo zu veröffentlichen: Ein faszinierendes Solodebüt! Eine ansteckende Spielfreude, energiegeladene explosive Improvisationen, eine Offenheit für Jazztradition und Experimente verbinden sich auf diesem...

ALLE NEUERSCHEINUNGEN

446: ANGELIKA NIESCIER. Chicago Tapes

Recorded May 5 and 6, 2025, at Transient Sound Studio, Chicago, by Vijay Tellis-Nayak.

448: ALEXIS MARCELO. Solo Piano

Recorded January 12, 2025, at Oktaven Audio, Mount Vernon, NY, by Ryan Streber.

447: FRED FRITH – MARIÁ PORTUGAL. Matter

Recorded at The Loft, Köln, on June 8, 2023, by Christian Heck.

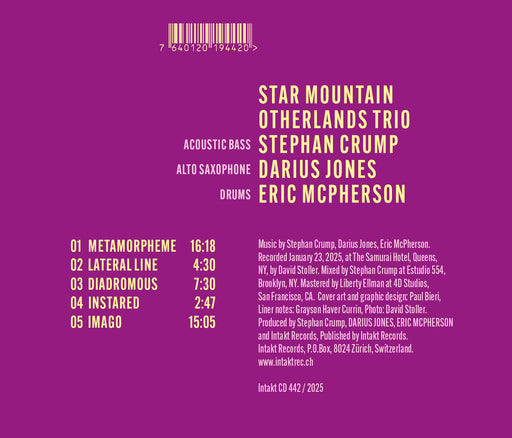

442: OTHERLANDS TRIO. Star Mountain

Recorded January 23, 2025, at The Samurai Hotel, Queens, NY, by David Stoller. Mixed by Stephan Crump at Estudio 554, Brooklyn, NY.

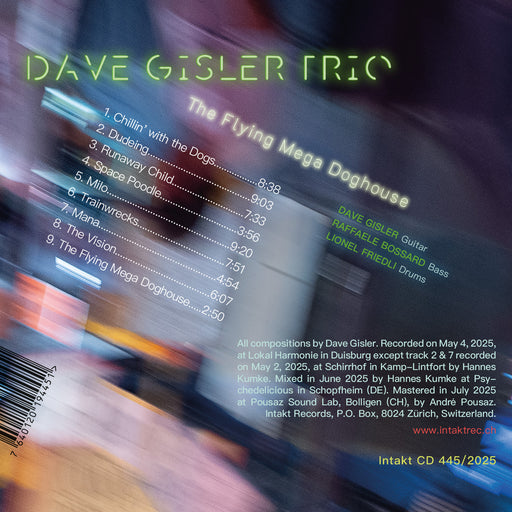

445: DAVE GISLER TRIO with RAFFAELE BOSSARD and LIONEL FRIEDLI. The Flying Mega Doghouse – LIVE

Recorded on May 4, 2025, at Lokal Harmonie in Duisburg except track 2 & 7 recorded on May 2, 2025, at Schirrhof in Kamp-Lintfort by Hannes Kumke.

444: SYLVIE COURVOISIER – WADADA LEO SMITH. Angel Falls

Recorded and mixed on October 12, 2024, at Oktaven Audio, Mount Vernon, NY, by Ryan Streber.

Let customers speak for us

NEUE MUSIK ENTDECKEN

Fördern Sie die Zukunft des Sounds.

Unterstützen Sie Künstler*innen, nicht Algorithmen.

Mit unserem Discovery-Abonnement können Sie jeden Monat neue Perspektiven gewinnen.