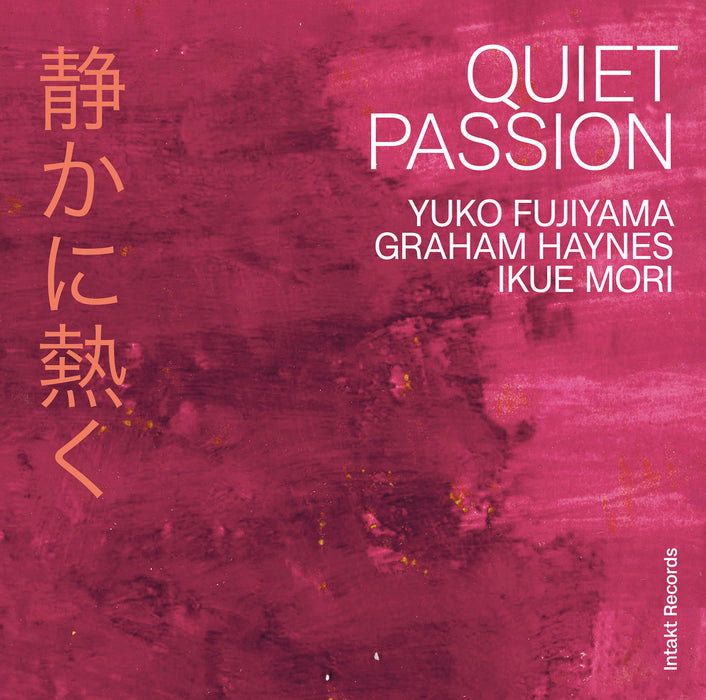

387: YUKO FUJIYAMA – GRAHAM HAYNES – IKUE MORI. Quiet Passion

Intakt Recording #387/ 2022

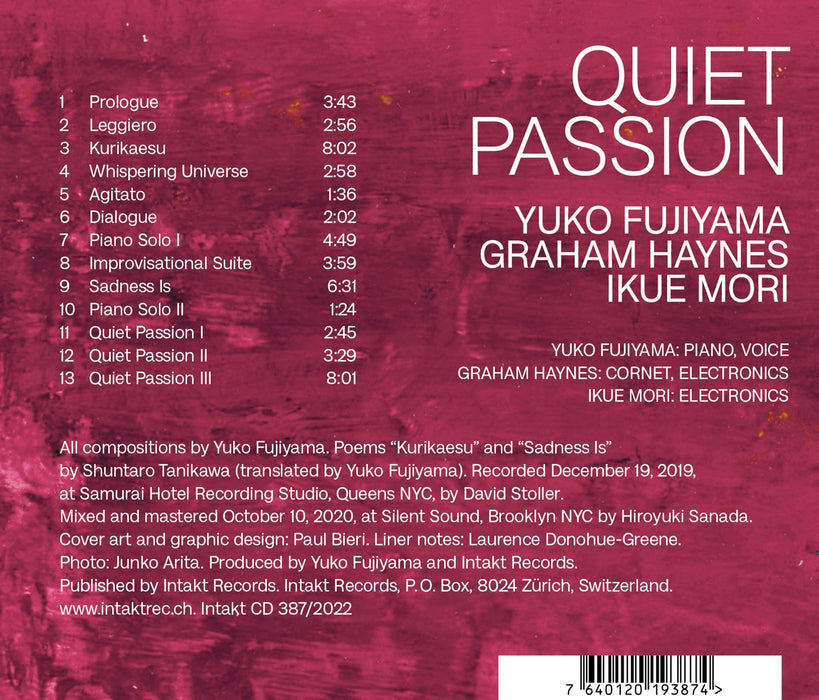

Yuko Fujiyama: Piano, Voice

Graham Haynes: Cornet, Electronics

Ikue Mori: Electronics

More Info

Mit «Quiet Passion» veröffentlicht die Pianistin Yuko Fujiyama nach längerer Veröffentlichungs-Pause endlich wieder ein Album als Leaderin. Für diese neue und willkommene Ergänzung ihrer spärlichen Diskografie lädt Yuko die grossen Innovatoren Graham Haynes am Cornet und die Elektronikerin Ikue Mori ein. Das Album ist eine Mischung aus Klaviersolos, Duos und dem ausserordentlich phantasievoll agierenden kollektiven Trio, das dicht gewobene Minia- turen spielt. «Quiet Passion» lässt sowohl im Titel als auch in der Musik eine doppelte Absicht erkennen: eine Kreuzung von Emotio- nen, die die drei Musiker:innen eindrucksvoll kreieren. Zur Besetzung sagt Yuko: „Good musicians listening to one another. I like totally free, because - I’m free, and anything I hear at that moment is allowed. ” Laurence Donohue-Greene schreibt in den Linernotes: „Es mag 17 Jahre gedauert haben, Schichten und Jahrzehnte von Ein- flüssen von Cecil Taylor und Marilyn Crispell bis hin zu Beethoven und dem japanischen Komponisten Takemitsu abzuschütteln, aber sie hat den Kern eines sehr persönlichen Stils gefunden, als ob sie in sich selbst einen fein geschliffenen Diamanten entdeckt hätte. “ Ein typisches Merkmal von «Quiet Passion»: den Hörer in Atem zu halten, wobei jedes einzelne Stück eine magische Anziehungskraft ent- faltet.

Album Credits

Cover art and graphic design: Paul Bieri

Liner notes: Laurence Donohue-Greene

Photo: Junko Arita

All compositions by Yuko Fujiyama. Poems "Kurikaesu" and "Sadness Is" by Shuntaro Tanikawa (translated by Yuko Fujiyama). Recorded December 19, 2019, at Samurai Hotel Recording Studio, Queens NYC, by David Stoller. Mixed and mastered October 10, 2020, at Silent Sound, Brooklyn NYC by Hiroyuki Sanada. Intakt Records, P. O. Box, 8024 Zürich, Switzerland. www.intaktrec.ch Disc and packaging by Adon Production AG. Produced by Yuko Fujiyama and Intakt Records. Published by Intakt Records.

Adventurous jazz pianists are all too often compared to the great Cecil Taylor. Years after his death, the master remains a mile-marker, his name almost an adjective for the indescribable.

But sometimes it fits. Taylor's music brought Yuko Fujiyama to the outskirts of free improvisation, so much so that years ago she could be seen at his concerts, silent and in rapture, a small white dog named Yuki on her lap, all four eyes focused on the shaman on the stage. "Maybe for her it was a lullaby," Fujiyama said with a laugh, remembering her long-since-passed canine companion. "She was very quiet except once, I went to see Shelley Hirsch and she jumped up on the seat." Fujiyama, speaking by video call from Japan, imitated a howl.

After discovering Taylor's music in 1980-she heard drummer Jerome Cooper playing a recording in his East Village apartment on her first trip to New York City and, seeing her transfixed on the street, invited her up to listen the piano maverick became a model and inspiration for Fujiyama's approach to free jazz. But her piano hadn't been heard, at least not in public, for more than 15 years when Innova Recordings released her Night Wave in 2018 and then it was a very different approach to playing and to leading a group. But Taylor was still a factor and in a roundabout way was key to Fujiyama's long hiatus. After putting a pause on public performance in the early 2000s, Fujiyama retreated to her apartment in the Bronx, where she has lived since making New York her permanent home in 1987, and retreated to her own piano, working on developing new ideas.

"I was so happy doing that free improvisation, I love that, but from 2000, I wanted to do my own compositions," she said. "I was trying to compose, but I didn't think it would take so long. Finally, I thought it was OK to start to perform. I thought, 'my composing isn't so good, but maybe it is OK.'"

During her hiatus, she also made visits to Japan, to see her parents in Sapporo and, as it happens, replace old inspirations with even older ones.

"I'm very impressed by Cecil Taylor," she said. "Cecil changed my life. My music was very influenced by his music but around 2000 I started to think, 'this expression is not the experience of my whole.' I started to look for my language. I thought, I'll start again.

"Cecil is so high energy, it is so amazing," she continued. "I think that's an energy everybody has inside. He pulled that out from me. That root is American jazz. That's not me. What I found is more space. I started to work in Japan with Butoh dancers. The way they move their bodies, feel the energy from the space, I feel that is somewhere I want to go. I feel it is Asian expression."

Those influences came to the surface on Night Wave (which was dedicated to Cooper) and are present again on Quiet Passion, released by Intakt last spring. Night Wave featured a couple of players who may well have related to Fujiyama's new Asian approach-violinist Jennifer Choi and percussionist Susie Ibarra along with Graham Haynes on cornet and flugelhorn. While he may have been an ethnic and gender outlier in the lineup, he fit into Fujiyama's concept. "We can share the space," Fujiyama said of Haynes. "His roots are groove but he has a common space with me. He has a lot of silence in his music. I assume his groove is happening but it's similar to a Butoh dancer's breathing."

Haynes returns for Quiet Passion, along with the Japanese-born electronicist Ikue Mori, with whom Fujiyama has occasionally played since the '90s. She is quick to point out, though, that the expression she sees as Asian isn't uniquely Asian, citing other jazz pioneers with an understanding of open space in their music -Marilyn Crispell, Roscoe Mitchell, Wadada Leo Smith - as well as her own bandmates on the two records she has made since coming out of professional seclusion.

"It is all human expression, breathing, feeling the space, listening to silence," she said. "It is not all about race, but Eastern expression. I was always frustrated in New York City that it is not well known."

Quiet Passion builds downward from Night Wave, with more space in the music and an ethereal atmosphere created by Mori's processed drum machines and Haynes' electronic effects. It is a beautifully serene record, sometimes active but never anxious, anchored by Fujiyama's readings of the contemporary poet Shuntaro Tanikawa (translated by Fujiyama into English).

That wonderful realization of her new approach isn't the only way Fujiyama is, at 68, redefining her career. This fall, she registered a nonprofit, Contemporary East, which will make its programming debut this month at Roulette, setting into motion another new aspect of her career, that of event producer. The first of the new organization's efforts will consist of performances by musicians who are either Asian or at least, to borrow her phrase, "feeling the space." Appearing over the two nights will be artists familiar to New York stages...

These three are New Yorkers with roots in jazz and experimental music. Graham Haynes, the son of drummer Roy, has placed his cornet and electronics in a dizzying range of music, including early straightahead dates. Japan-born pianist Yuko Fujiyama, the ostensible leader of this recording, had her life turned around by hearing Cecil Taylor in 1980 and his music remains a strong influence. Mori (electronics, just announced as a 2022 MacArthur Fellow) may be most known for working with Arto Lindsay in the downtown no-wave band DNA. Together, they are in a word, free.

The pieces are mostly short, with Fujiyama's interjections in Japanese and English. On “Kurikaesu”, the longest composition, cornet and piano engage in spare interplay, with a gently bubbling electronic bed and words from Japanese poet Shuntaro Tanikawa. "Dialogue" also features their contrasting playing. The short "Whispering Universe" finds Fujiyama going inside her instrument to play the strings while Mori provides atmospheric electronics and Haynes gets moody. "Agitato" is all piano and electronics and nearly violent for a whole minute and a half; here the aforementioned Taylor looms large. Fujiyama has two piano solos on the disc and they reveal her own darting and idiosyncratic style. It is a good way to hear this uncompromising musician, who hasn't recorded all that much (and took a long sabbatical between 2000 and 2017).

The first half of "Improvisational Suite" has Haynes playing through echo effects under busy piano and electronics. Miles Davis isn't in the building, but he is down the road a piece. The second half is far more sparse. The three parts of the title track live up to their name, full of space and meditative, a touch sad, with the musicians in various combinations. The long third segment has all three working together to round out the disc...quietly.

La pianiste japonaise Yuko Fujiyama m’apparaît comme une pianiste, et une musicienne, d’une envergure assez considérable. La rencontre, à New York en 1980, de la musique de Cecil Taylor fut un bouleversement dans sa pratique. Mais elle n’adopta pas le jeu foisonnant et expressionniste de cet immense créateur, son jeu apparaissant au contraire concis, précis, réfléchi et posé, et le piano sonne merveilleusement bien. Pour ce disque qui comprend treize pièces, la pianiste s’est entourée du grand trompettiste Graham Haynes ici uniquement au cornet, et qui ajoute quelques manipulations électroniques aux côtés de la spécialiste Ikue Mori, entendue récemment avec Fred Frith (Intakt CD 352). Il comprend treize pièces et alterne trios, duos et deux solos. Magnifique !

https://culturejazz.fr/spip.php?article3852

Het bleef jaren stil rond de Japanse pianiste Yuko Fujiyama (William Parker, Wadada Leo Smith) maar ze behield de passie. Getuige hiervan is deze opname die ze maakte in de New Yorkse Samurai Hotel Recording Studio op 19 december 2019 in gezelschap van Graham Haynes (cornet, electronics) en Ikue Mori (electronics).

De vermelde electronics zijn weliswaar beperkt tot een absoluut minimum. Het zijn eerder de stiltes die doorwegen. Deze worden hoofdzakelijk opgevuld met de abstracte pianoriedels van Fujiyama afwisselend solo, in duo en ook al eens in trio. Tweemaal wordt er “gemusiceerd” rond een gedicht van Shuntaro Tanikawa, haast geruisloos ingesproken door Fujiyama. Door de subtiele enscenering ontstaat een homogene en vooral suggestieve uitstraling getekend door een zekere zwaarmoedigheid. Wie Haynes kent van bij M-Base Collective en zijn hiphop uitstappen moet even bijsturen.

https://www.jazzhalo.be/reviews/cdlpk7-reviews/various/intakt-special/?fbclid=IwAR2LyMEUCDf9X9AZT_l9w8mll8Wi10GPfu2tqQlQzWKIEloK0ltFVq-jyfo

Ein sicheres Gespür für Transparenz, klangliche Essenz und die Bedeutung des Raumes zeichnet diese Aufnahme aus. Und der Pianistin Yuko Fujiyama (verantwortlich für alle 13 Tracks dieser CD) gelingt es auch vorzüglich, eine abstrahierende, avantgardistische Tonsprache mit einer aussparenden Klang-Poesie zu vereinen. Zudem führt sie Elemente des freitonalen Jazz - sie war in früheren Jahren stark von Cecil Taylor beeinflusst - und der Neuen Musik zu einer stimmigen Synthese. Fujiyama (Piano, Stimme) konnte für >>Quiet Passion<<< noch die Elektronik-Spezialistin Ikue Mori und Graham Haynes (Kornett, Electronics) gewinnen. Ein Ensemble, das mit seiner klanglichen Delikatesse, seinem ästhetischen Einverständnis beeindruckt. Das Album bietet Werke für Piano solo, Duo-Begegnungen oder wachsames Trio-Spiel. Fujiyamas Arbeit am Flügel zeichnet sich durch eine scharfumrissene, klare Pianistik aus, Ikue Mori verleiht ihrer (Laptop-)Elektronik nicht selten einen >>organischen<«, naturnahen Charakter, und Graham Haynes gewinnt vor allem mit den Legato-Noten seines leuchtenden Kornetts. Bei zwei Kompositionen rezitiert Yuko Fujiyama zwei Gedichte des zeitgenössischen japanischen Lyrikers Shuntaro Tanikawa. verwebt gelungen gesprochene Poesie und instrumentale Sprache.

Sporadically recorded, Sapporo-born, New York based pianist Yuko Fujiyama continues to probe unexpected territories. Moving from acoustic sessions with the likes of Jennifer Choi and Susie Ibarra, she commits to an electronic environment on the three-part suite and other tracks here. Confirming the change is the addition of fellow New York/Japanese expatriate Ikue Mori’s electronics, and associate Graham Haynes, adding programming and effects to his cornet thrusts.

Although firmly committed to the Free Jazz matrix, maturity has contributed balance and dynamics to the pianist’s playing. Because of this Mori’s output which can encompass outer-space-like crackles as much as gentle repercussion, reminiscent of temple bells or winds whistling through dense foliage coms up against simple piano riffs or metronomic rumbles. Then on “Kurikaesu”. onomatopoeic vocal projection coupled with scrunching voltage vibrations, portamento brassiness and chunky keyboard emphasis undulate alongside Fujiyama intoning descriptive poetry in English and Japanese. But even here her sympathetic reading and her three descriptive solos are auxiliary to group interaction.

Crucial to this is “Quiet Passion’, a three-part suite that gradually builds up from relaxed piano chording alongside programmed watery splashes and slides that cushion portamento brass breaths that is then modified to focused piano patterns which presage an echoing rumble from the electronics. Finally “Quiet Passion III” culminates in low-pitched drama as half-valve strains from the cornetist, electronic swirls and squeaks and piano reverberations reach a climax. As the theme shifts from keyboard to valves to synthesis the profound interchange is confirmed.

“Whispering Universe” and “Sadness” are other instances of this strategy mixing mellow with mercurial. Haynes’ playing is central and upfront beside distant pianism and muted electronic burbles. Goosing his output with electronics, the cornetist’s rippling slurs and expressive shakes define both part of the trio’s sound equation.

It’s a shame Fujiyama doesn’t but out more discs. But if all her sessions would be like Grand Passion, extended waits can be forgiven

https://www.jazzword.com/reviews/yuko-fujiyama-graham-hayes-ikue-mori-2/

Recommended New Releases

Zoh Amba-O LIFE, O LIGHT (577 Records)

Albert Ayler-Revelations: The Complete ORTF 1970 Fondation Maeght Recordings (Elemental Music)

Will Bernard-Pond Life (Dreck to Desk)

Camille Bertault/David Helbock-Playground (ACT Music)

Satoko Fujii/Joe Fonda-Thread of Light (FSR)

Yuko Fujiyama/Graham Haynes/Ikue Mori-Quiet Passion (Intakt)

Mary Halvorson-Amaryllis & Belladonna (Nonesuch)

Darren Johnston-Life in Time (Origin)

Miles Okazaki Trickster-Thisness (Pi)

Álvaro Torres-The Heart Is The Most Important Ingredient (Sunnyside)

Laurence Donohue-Greene, Managing Editor

Dave Brubeck Trio-Live From Vienna 1967 (Brubeck Editions)

Silke Eberhard's Potsa Lotsa XL & Youjin Sung-Gaya (Trouble in the East)

Dave Gisler Trio-See You Out There (with Jaimie Branch and David Murray) (Intakt)

HÜM-Don't Take It So Personally (Losen)

Charles Mingus-The Lost Album from Ronnie Scott's (Resonance)

PLOP & JUNNU-Eponymous (Fiasco)

Shake Stew-Heat (Traumton)

Steamboat Switzerland-Terrifying Sunset (Trost)

Natsuki Tamura-Summer Tree (Libra)

Yamash'ta & The Horizon-Sunrise from West Sea (London-Wewantsounds)

Andrey Henkin, Editorial Director

Yuko Fujiyama, quiete passioni

Note sparse La pianista giapponese ha iniziato la sua vera vita di musicista nel 1980. Ora torna con l'album «Quiet Passion»

Yuko Fujiyama è la pianista «avant», informale no, piuttosto logica di una logica free, che fa un po' la leader e scrive 11 tracce su 13. Ha 68 anni ma solo dal 1980 ha iniziato la sua vera vita di musicista ed è stata l'illuminazione dell'ascolto di Cecil Taylor a offrirle le chances che desiderava. È oggi una delle nuove eroine del pianismo jazz-oltre-il-jazz. Con cultura classica-contemporanea e attenzione a evitare pomposità. Dà forse il meglio in questo cd nel brano intitolato Agitato. Ma agitato non è il suo eloquio come non lo è quello dei suoi due partner. Graham Haynes è il cornettista adorabile che ben conosciamo, tutto desiderio di liricità e orgoglio di conoscenza delle avanguardie. Ikue e Mori la conosciamo da ancora più tempo come la regina dell'elettronica nel campo non territorializzato della scena Downtown di New York, della musica di ricerca in generale, non corrucciata, scorrevole, amabile. Insieme i tre spiegano che cosa intendono col concetto di Quiet Passion (Intakt), la passione silenziosa o pensosa o assorta. Yuko in due brani è anche vocalista con un >> non particolarmente originale.

https://ilmanifesto.it/yoko-fujiyama-quiete-passioni

Pianist Yuko Fujiyama does not routinely release music. When she does, it is always for a special purpose. This trio recording, Quiet Passion, was preceded by Night Wave (Innova Recordings, 2018) and, like her previous album, she is joined by cornetist Graham Haynes. The trio is completed by fellow Japanese- born expatriate Ikue Mori a longtime mainstay of New York's Downtown scene. Fujiyama, a Cecil Taylor devotee, has maintained the essence of Taylor's art but, through the years, she has stripped the great man's music down. Her music is not unlike a Japanese haiku which can capture, in seventeen syllables, the ethos of a much lengthier and thickset poem.

The music on Quiet Passion merges the improvisation of the acoustic instruments, Fujiyama's piano and Haynes' cornet, with electronics. Mori is a master of electronic processing who can mold her instrument to her will and not the other way around. Haynes investigates the possibilities of electronics here also. Listeners of his work with Hardedge (aka Velibor Pedevski) will be familiar with this blending of instrumentation. Fujiyama presents her work here in solo, duo and trio settings. Opening with a one-note blast of cornet, "Prologue" dives headfirst into a stuttering recitation which pulls in seemingly disparate directions, piano and cornet bouncing off a storm of electronic percussion. The music finds its level in this cooperative improvisation. The same can be said of the remainder of the tracks. The trio's work on "Whispering Universe" finds both Haynes and Mori manipulating the electric fields while Fujiyama works her piano's insides, all of which makes for a phantasmic sound. Fujiyama's two brief piano solo tracks reveal an ever-patient yet tenacious approach to a minimal, emblematic Cecil Taylor sound.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/quiet-passion-yuko-fujiyama-graham-haynes-ikue-mori-intakt-records

In 1980 bezocht Yuko Fujiyama (Sapporo, 1954) voor de tweede keer de V.S., de klassiek opgeleide pianiste zocht naar een woning om tijdelijk in New York City te verblijven. Zo kwam zij in contact met de muziek van pianist Cecil Taylor in de East Village en dat veranderde alles in haar leven. Het verblijf werd 6 maanden, ze werd een van Cecil’s beste discipelen. Cecil en zijn muziek veranderde haar leven in 1980 “I was so attracted to that piano sound and was under his influence for a very long time” aldus Yuko. In 1987 keerde zij terug naar New York waar ze nog steeds verblijft, tot halverwege de jaren ’90 bleef ze onder de invloed van Taylor tot muzikanten uit zijn omgeving haar vertelden dat Cecil altijd zei “Never copy” die twee woorden maakten een onuitwisbare indruk op haar op zoek naar haar eigen muzikale weg . Ze legde zichzelf een sabbatical op na haar album “Re-entry” uit 2000, in 2017 was er haar comeback met “Night Wave” en dit is haar tweede comeback. Ze nodigde Graham Haynes uit die ook op haar vorige album meedeed, hier speelt hij kornet en Ikue Mori op elektronica, het album bestaat uit solo, duo en trio improvisaties.

Het album begint met “Prologue” een duo van Yuko en Graham, duidelijk een kwestie van aftasten en reageren. In “Kurikaesu”(herhaling) speelt Yuko niet alleen piano maar reciteert ze een gedicht van de hedendaagse Japanse dichter Shuntaro Tanikawa, ondersteunt door de kornetfrasen van Haynes en de elektronische erupties van Mori, een leuk idee maar helaas is de tekst nauwelijks te verstaan. Dan liever een nummer als “Piano solo I” met uiteraard Yuko solo, weids uiteen waaierende klanken in verschillende patronen gegoten. Met de muziek van Cecil Taylor heeft het niet (meer) zoveel te doen en dat is misschien maar beter ook, copycats zijn er al genoeg. Een ander leuk nummer is ”Agitato”, een slechts anderhalve minuut durend agressief piano/elektronica duo dat wonderwel werkt. Er zijn invloeden van hedendaagse klassieke muziek en natuurlijk avantgarde jazz maar het resultaat is 100% Yuko vermeldt het cd boekje en daar kan ik mij wel in vinden, maar vergeleken met het uitermate geslaagde album Piano Solo van Elias Stemeseder, dat ik ook recenseerde, is dit album duidelijk minder. Het antwoord ligt zoals altijd bij de luisteraar.

https://rootstime.be/index.html?https://rootstime.be/CD%20REVIEUW/2022/APR1/CD120.html